This piece was written by Teagan Waymouth, one of the Cinema Rediscovered 2025 Roaming Reporters – a talent development scheme in partnership with BFI Film Academy South West.

I had the pleasure of attending Cinema Rediscovered 2025 in Bristol to see an array of carefully curated films, beautifully introduced and restored. Of the twelve I watched, two independently made films stood out for their representations of sexual relationships and identity. Desert Hearts and My Beautiful Laundrette are examples of stories with queer themes colloquially intertwined into the protagonists’ lives— an unfashionable concept for the 80s.

Desert Hearts, 1985, Donna Deitch

As the title promises, we are served a desert romance between Cay, a young non-committal cowgirl whose queerness is commonplace and assured to those who know her well, and Vivian, a mature scholar stiffened by her profession and loveless marriage, who boards at the same ranch whilst seeking a divorce.

The Western, subverted of its core essences—(masculine) self-discovery, individualism, and identity — is found in this cult lesbian film from 1985, set in 1950s Rockabilly Nevada.

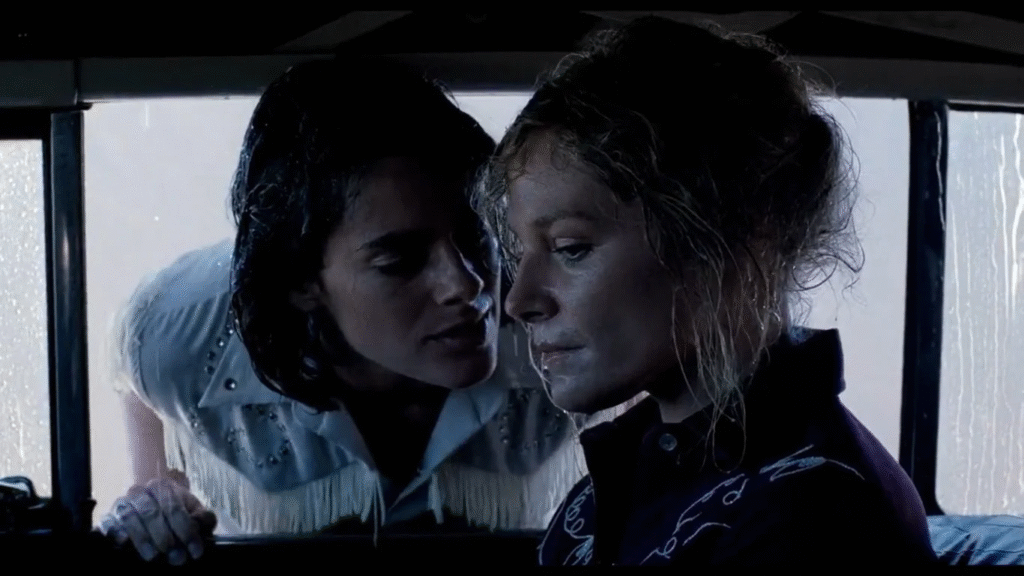

Introducing Desert Hearts at the festival was co-curator Rosie Beattie, who said the film’s lesbianism is given the Hollywood treatment: unconcealed, unapologetically queer, and, notably for the period, non-coded. Having built their companionship, the two women, not yet lovers, fall into a beautifully sensual kiss in the rainy dusk, captured in a close-up. Vivian is hesitant, afraid of her own desires whenever she is confronted with outright intimacy. Often, the film uses physical space as a psychological confrontation, with Vivian’s initial comment on her new environment referring to the amount of space she isn’t used to.

It’s an unrealised opportunity to indulge in her own undiscovered identity; the vast desert landscapes acting as a vessel for freedom and discovery emblematic of Westerns, framed here in a Sapphic context. An exploration of vulnerability, fear, and love, all in one of the first widely released films by a woman director about a positive lesbian relationship rather than the usually tragic, fetishised affairs.

As Dietch sought out, it doesn’t end in a “bisexual love triangle or a suicide”—a complete breakthrough in representing queerness as just another love story.

My Beautiful Laundrette, 1985, Stephen Frears

Also released in 1985 as a turning point in queer cinema, My Beautiful Laundrette is a social realist comedy about Omar, a British-born South Asian, who has been given the opportunity by his wealthy uncle Nasser to manage and refurbish a launderette in London.

Omar recruits his old friend, the white working-class Johnny — and they’re gay, by the way. Despite this being a rather casual affair, their relationship is far more political, in line with the film’s core ideas about money, power, and identity. As Britain was under the thumb of

Thatcherism, a new free market brought about the spread of an entrepreneurial middle class, taken advantage of by Omar’s family, contrasting with the struggles of the white working class that

foregrounds the film’s racial tension.

Disconnected from his British-Pakistani heritage, Omar is unable to speak his ‘own’ language and is more determined to rise through the ranks of his family and advance onto a new economic vitality that gives way for social mobility; a power over the skinheads who claim ‘they came over here to work for us’ and lament Johnny for

being attached to Omar‘s ‘p*ki’ launderette.

However, Johnny is interested in what the laundrette offers him: a fresh start, economic stability, purpose, and, suddenly, an outlet and escape for his queerness. A symbolic place of freedom away from racial tension, the launderette is also a second chance for Johnny to rekindle his relationship with Omar and, by extension, the Asian community as an ex-national front supporter. For Omar, it’s a chance to prove his legitimacy as an entrepreneurial man.

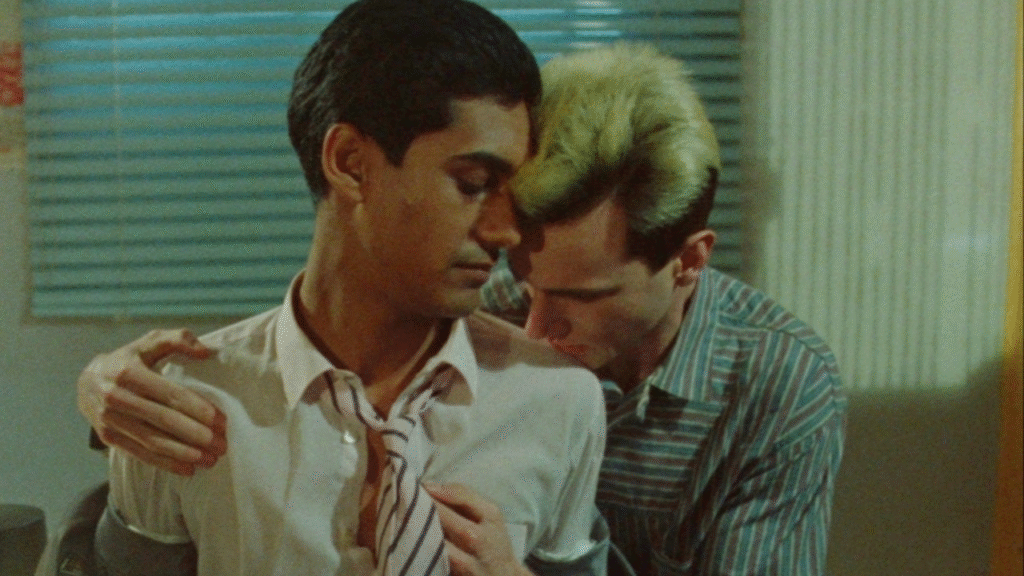

One could call their relationship a queer love story, but the queerness is rather offhand. During the refurbishment of the launderette, veiled in nightfall, Johnny takes Omar’s face and kisses him; no music, quick cuts, or sensationalised performance. Their sex traverses into the suds, neon lights, and gleaming modernities once the launderette is finished, and they abandon acting as grand openers, the ceremonial champagne symbolically poured from Johnny’s mouth to Omar’s.

Though they conceal the relationship from their peers, which would otherwise be a dangerous revelation, the film neither attempts to condemn nor moralise their sexuality or foreshadow a tragedy. This casual display of queerness is part of what makes this film so remarkable during the media fearmongering of AIDS and predating the homophobic Section 28.

Within the context of My Beautiful Laundrette, it is more befitting as a capsule (and critique) of Thatcher-era Britain, narratively threaded with gay desire.

The ninth edition of Cinema Rediscovered is presented by Watershed and partners with the support of the BFI Audience Projects Fund, awarding National Lottery funding, and principal sponsors Park Circus and STUDIOCANAL.