To stay on top of all the films, talks and events that took place during the five days of this year’s Cinema Rediscovered festival which took place in July, we sent writer and film critic Nathan Hardie to cover all the goings on at Watershed’s annual celebration of archive cinema. Here are his reports from each day of the festival!

Day 1

My name is Nathan aka “HardieWrites” and it has been only four months since my first article about The Godfather’s 50th Anniversary was published, making it just over a year since I chose to seriously pursue my creative endeavours. Therefore, to have been invited to watch so many great films and lectures over these five days is still a very surreal feeling, placing me in a reflective mood about my journey.

Discussing her own journey in the official opening event was Writer and Broadcaster Samira Ahmed. Introduced by Bristol Ideas’ Andrew Kelly, Ahmed passionately discussed the films that moulded her childhood through to how she shares these pictures with her own children. I was pleasantly surprised at the significant influences of James Bond & The Carry On series which had been introduced to me by my mum as a child too, proving that despite their many flaws these movies are a British institution that have stood the test of time. The significant issue linking the two is how women are portrayed in cinema, something Ahmed eloquently weaves in whilst bouncing from film to film.

With the aid of a slide show, she proved how well 90’s Disney characters such as Pocahontas, Mulan & Esmeralda convey emotion through expression alone as well as their important role featuring themes of abuse and harassment appropriately. These stories are the subject in some of her favourite films set in the workplace too, such as Dolly Parton’s Straight Talk and Working Girl starring Sigourney Weaver. Throughout the hour-long lecture, she also provided anecdotes of her past interviews and a heart-warming encounter with film critic Philip French as well as impressively squeezing in a quotes quiz and Q&A.

Altogether, a fascinating insight into an inspirational journalist adding many films onto my watchlist – the lecture can be found here.

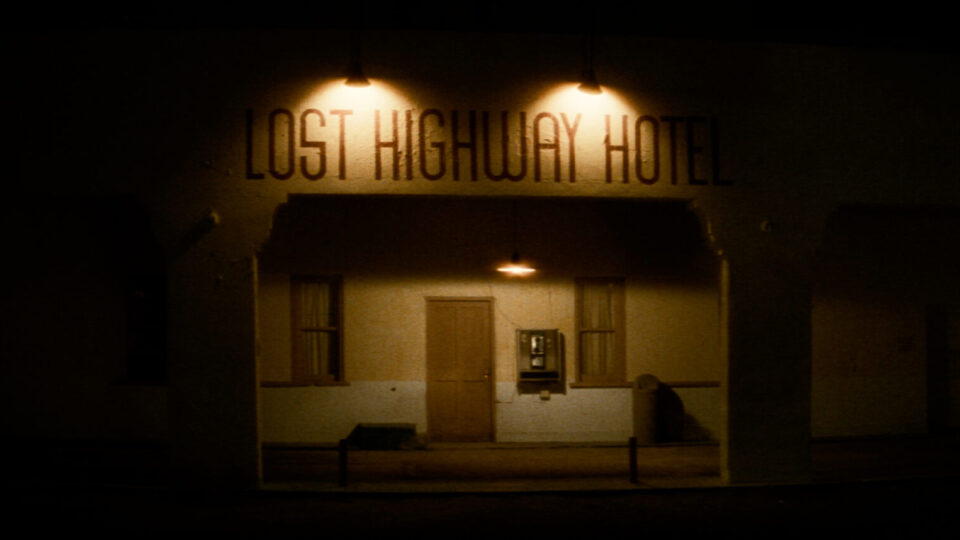

Fortunately, I can now remove one movie from my watchlist and that’s David Lynch’s Lost Highway. Restored after being released over 25 years ago, the audience was treated to a special introduction from the legendary director himself, building on an already special event. Starring Bill Pullman as saxophonist Fred Madison and Patricia Arquette as his always glamorous wife Renee, the story starts with the couple discovering a video tape containing footage of their L.A apartment. Vulnerable from the invasion of privacy, they call the police but there’s no sign of break-in or anything missing. After another tape turns up, the narrative flips on its head and I was suddenly transported to the lost highway.

Just as I thought I had a grasp on the situation, another twist comes my way

Just as I thought I had a grasp on the situation, another twist comes my way. Like many of Lynch’s other works, this journey is more metaphorical whilst successfully breaking story structure and bending genres from erotic thriller to supernatural horror. There’s an incredible performance by Robert Loggia that strides the line of hilarious and downright insane. The whole movie is accompanied by a fantastic soundtrack composed by Angelo Badalamenti to provide a helping hand on how to feel when you’re still figuring out what’s going on.

Still figuring out what’s going on brings me back to my own journey. Whilst I’m certainly not comparing my path to a David Lynch film, I share that same feeling of wondering how on earth I got here. Yet, by the end of the movie, everything seemed to click and I was able to make some sense of the action that had unfolded. I look forward to when my journey finally clicks and I can share it as deftly as Samira Ahmed does, but for now I will just try to enjoy the ride.

Day 2

From the year 1934 to 1968, Hollywood adhered to a set of strict industry rules known as The Motion Picture Production Code (or Hays code after Will H. Hays, the President of Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America – MPPDA). This code was split into two parts, Don’ts and Be Carefuls, in an attempt to prevent “lowering the moral standards of those who see it”, specifically those with more “susceptible minds such as women, children and the lower-class”.

These restrictions included no swearing, no drug trafficking and no sexual perversion, a topic which ranges from nudity to homosexuality to relationships between different races. Heavily influenced by the Catholic church, the code caused careers to disappear and widespread disapproval as audiences had already experienced talkies without the reins on. This is the era known as Pre-Code, a period I became heavily invested in on my second day of the festival.

Pre-code Hollywood: Rules are Made to be Broken is a strand of Cinema Rediscovered curated by film critics Christina Newland and Pamela Hutchinson containing five films released between 1929 and 1934: Jewel Robbery, Red-headed Woman, Baby Face, A Free Soul and Blonde Crazy. In their talk, they discussed what drew them into Pre-Code cinema, with Hutchinson a fan of rule experimentation whilst Newland was driven more by a passion for the crime genre alongside female desire, and provide a censorship timeline starting from 1915 when films were deemed not protected under free speech.

They also detailed the cultural and political impact of the Hays code, pontificating where cinema and the US landscape as a whole could have progressed if films had continued to break barriers put in place by a homogenised society.

One of the main groups heavily affected were women, who are the stars of two films I watched on Thursday (three counting Marlene Dietrich’s entertaining ensemble Shanghai Express from the strand When Europe Made Hollywood). Norma Shearer was a pioneer of Pre-Code cinema, frequently playing roles of independent, sensual women such as 1931’s A Free Soul. Based on the book by Adela Rogers St Johns, Shearer portrays Jan Ashe, the free-spirited daughter of alcoholic lawyer Stephen Ashe (Academy Award winner Lionel Barrymore). Whilst keeping an eye on him at work, she falls for gambler and accused party Ace Wilfong (Clark Gable) despite already being engaged to polo player Dwight Winthrop (Leslie Howard).

The dynamic between father and daughter outcast from the family was particularly intriguing, and its dramatic theme of independence versus dependance holds up well today

The premise alone breaks many of the code rules already, but her laissez-faire attitude towards sex had censors reeling as she suggestively asks Gable to place his arms around her. The dynamic between father and daughter outcast from the family was particularly intriguing, and its dramatic theme of independence versus dependance holds up well today.

However, as highlighted by Newland in the film’s introduction, a version of the code was still in place during production, leading to a more sanitised ending, something that particularly hindered Blonde Crazy too. Fronted by Joan Blondell in a double act with James Cagney, Blonde Crazy is about a bellhop and maid pulling scams trying to elevate themselves into high society.

Blondell’s character Anne Roberts is quick-witted, sharp talking and puts up with no nonsense from Cagney’s character Bert Harris, frequently slapping him when his flirtatious antics get out of line. For the majority of the picture, Roberts is unflappable, forging her own path whilst solving both of their problems. Yet, to satiate the studio, this piece regresses Roberts to the mean of doting, distressed housewife. Fortunately, it does not undermine the big laughs or on-screen chemistry between Blondell and Cagney.

Altogether, the importance of these Pre-Code films are the inspiration for Post-Code Cinema. We’ve eventually reached a time where women can be accurately represented, be the star of the show and not have everything wrapped up at the end by getting married in a church. There’s still censorship today in China and Russia for example, but progress has been made and Pre-Code Cinema is a part of the foundation.

Day 3

Identity is an aspect of my life that I grapple with on a daily basis. Throughout my childhood, I had passed as white, with the questions of my ethnicity only rearing its head when my curly hair grew out. Since broadening my horizons and entering more diverse spaces as an adult, I can finally understand what those teasing comments about my lips really alluded to. Yet, as I tick those mandatory boxes on inclusion forms to ensure corporations aren’t interviewing the same five faces (but hiring them anyway), I still feel like I don’t fit in anywhere. It’s these notions that underline one of the strangest double bills I’ve seen in an intimate Day 3 of Cinema Rediscovered.

My evening started with Finding Christa, a documentary from 1991 written, directed and starring L.A artist Camille Billops. During Billops’ twenties, she gave up her 4-year-old daughter Christa for adoption and travelled to Egypt with James Hatch (soon to be husband and co-director of this piece), further pursuing her artistic craft. 20 years later, Billops received a tape from Christa containing a song and a request to meet. This film details the thoughts and feelings of family and friends during such a tough time alongside Christa’s childhood with her foster family, before they finally reconnected.

Admittedly, some of the interactions feel re-enacted or there had been multiple takes as Billops’ friends are not trained actors, but you cannot replicate the raw emotion on display from the various talking heads. Christa’s foster mum, an Oakland Jazz Singer known as Rusty Carlyle, is especially passionate describing Christa’s upbringing as well as the importance of finding the birth mother despite the potential consequences. It’s a powerful piece about choice and identity from Billops’ perspective, feeling obligated to have the child despite being a single mother and accepting life would be better for her child elsewhere, but also for Christa, struggling with that feeling of belonging and that a part of you is missing.

Inexplicably, this feeling of belonging elsewhere is how the second feature shown at the Wonderful 20th Century Flicks began.

Written and directed by British horror legend Clive Barker, Nightbreed stars Craig Sheffer as Aaron Boone, a man frequently haunted by a fantastical place containing monsters called Midian, despite the pills he’s taking prescribed by Dr. Philip Decker (David Cronenberg). Yet, these nightmares turn out to be a reality when Boone discovers Midian under a cemetery outside of town whilst escaping from the police after being accused of murder. Now, the livelihood of the Nightbreed is at stake with only Boone and his plucky, empathetic girlfriend Lori (Anne Bobby) can save them.

What unfolds is over 90 minutes of blood, gore, explosions and body horror that refuses to take a breath. Chase scenes are accompanied by a tusked man playing the drums giving that extra intensity before heads literally explode in shootouts. The intricate details of each monster are incredible, some of which are only on screen for a couple of seconds.

There is so much crammed in here, yet several story points missed because of studio interference, highlighted by an excellent introductory speech from Adam Murray of Bristol Black Horror Club. Murray also brought attention to the several allegories regarding race and being outcasted from society shown in Nightbreed, something I especially agree with as it ramped up towards the third act.

It is beautiful that two completely different movies in style, tone and budgets can convey such emotions whilst both be uniquely entertaining

These two films presented the bittersweet feeling that my identity crisis is one of the significant factors I do have in common within marginalised communities. Yet, it is beautiful that two completely different movies in style, tone and budgets can convey such emotions whilst both being uniquely entertaining. Leaving 20th Century Flicks at midnight and having a group photo on the Christmas Steps also reminded me that I am a part of a community, one united by cinema.

Days 4 & 5

By the end of my Cinema Rediscovered journey, I had viewed 13 films and 4 lectures in 5 days – a very fulfilling if a little tiring experience. It was great listening to so many cinema experts and expanding my knowledge on so many underrated, hidden gems. In the closing weekend portion of the festival, however, it was time for some certified, well known Hollywood Classics.

Day 4 culminated with the thrilling duo of Double Indemnity and 1962’s Cape Fear whilst Day 5 was headed by one of the most well-known movies, Casablanca, and iconic western High Noon. Whether it’s from the Academy Awards, the IMDb Top 250 list or Martin Scorsese, these four films have been dubbed some of the best of all time. Therefore, I wanted to explore where they all succeed and what it really takes to make a Hollywood Classic.

First, let’s take a look at the characters. The tall, chiselled, white leading man was the staple at the time and here was no different (although Humphrey Bogart wore lifts to be taller than co-star Ingrid Bergman). What I found more intriguing is how internally conflicted they were rather than the standard self-assured all-American heroes. Gary Cooper’s Will Kane initially leaves town in High Noon to avoid a shootout is just one of the many reasons why John Wayne hates this film and I love it. Fred MacMurray’s Walter Neff doesn’t want anything to do with an insurance scam at the start of Double Indemnity, but he just can’t resist Phyllis Dietrichson. Played by Barbara Stanwyck, Dietrichson is also the female lead with the most depth, further proving that progressing past the token love interest makes movies a lot more interesting.

Tying memorable dialogue from a sharp, punchy script together with an intriguing, twisting story and you have the bare bones that makes up these great pictures.

Bearing this in mind, I believe the biggest strength of all four features are the villains and how the films create threats. High Noon’s real-time ticking clock leaves you stressfully waiting for an infamous gunslinger and trying to avoid being caught by Nazis in Casablanca or head insurance salesman Barton Keyes (excellently portrayed by Edward G. Robinson) in Double Indemnity has the audience on the edge of their seat.

My favourite, that elevates Cape Fear into this conversation, is Robert Mitchum’s Max Cady. Wearing a Panama hat and speaking with a thick southern drawl, Cady’s style is simple but distinctive. Always lurking in the background living in Gregory Peck’s head rent-free would be unnerving enough, but it’s the fact that he’s seemingly untouchable by the police that pushes anxiety levels to the max.

Each tense moment from Cape Fear, as well as Double Indemnity, is heightened by the accompaniment of piercing violins, yet they never distract from the on-screen action. High Noon is an outlier from most movies as it only repeats bars from the opening song ‘The Ballad of High Noon’ by Dimitri Tiomkin, which complements the western genre well and somehow adds to Kane’s increasing desperation each time it’s played.

This aspect of repetition is what Casablanca taps into most effectively, and why I believe it’s the most famous of the four. Using ‘As Time Goes By’ emphasises the love between Rick Blaine (Bogart) and Ilsa Lund (Bergman), helping develop their relationship every time we hear the song. It also goes in hand with the phrase ‘Play it again, Sam’, one of the many quotes tied around the film.

Having such a catchy script allowed the audience to do their best ‘Here’s looking at you kid’ impression, thus cementing it in the annals of pop culture to pass on to the next generation. Tying memorable dialogue from a sharp, punchy script together with an intriguing, twisting story and you have the bare bones that makes up these great pictures. Granted, it’s easier said than done to replicate all of this (I’ve not even mentioned cinematography or editing) but they’re all something I consider when I critique as well as writing my own stories.

These four films alongside the rest of the festival have stoked my passion for cinema and I hope they’ve helped you rediscover everything you love about film too.

This article also appeared as a series of daily articles on Rife Magazine.

About Nathan Hardie:

Nathan (aka HardieWrites) is a writer and producer from Bristol. Drifting away from a mathematics background, he is pursuing his passion for storytelling by creating screenplays, articles and the occasional poem. Nathan also loves discussing what he’s been watching, reviewing film, TV and theatre. A mental health advocate, he’s willing to open up about his anxiety and to keen help people do the same.