Lunchtime talk write-up

Posted on Fri 13 May 2016

Bridging the Gap Between Artists and Technologists

In Tarim's talk we visited the tongue-in-cheek ‘Land of Sweeping Stereotypes’, a land where a tribe of artists and a tribe of technologists live on different islands – occasionally meeting in no-mans land.

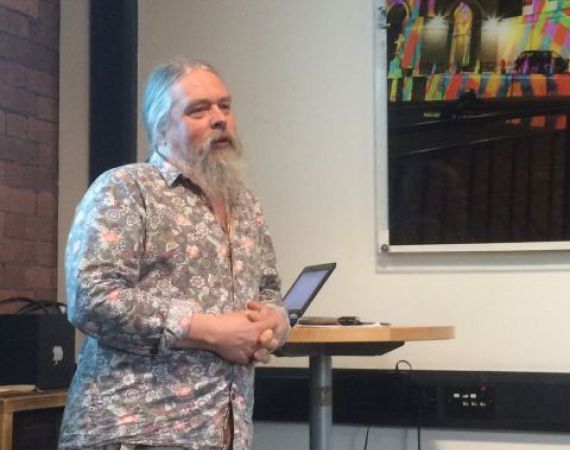

Tarim

Speaker

Tarim

Tarim creates Media Playgrounds - installations which people can both play with and build new and different places to play in.Tarim began his talk by inviting us to travel to the tongue-in-cheek ‘Land of Sweeping Stereotypes’ for the purpose of this talk, a land where a tribe of artists and a tribe of technologists live on different islands – occasionally meeting in no-mans land. Tarim identified himself as a member of the tribe of technologists, he has been writing software and collaborating with artists for 40 years, and regularly collaborates with other Studio residents. Here are five things I learned about integrating technology into creative practice:

1. We all make assumptions about what technology can do, often based on what we see in films, on TV or in sci-fi. Tarim explained that it can be difficult to know and to explain the difference between two things that might feel similarly achievable, when one is easy and the other virtually impossible.

2. “String is really, really good technology” – sometimes the best and most reliable technology is not what we would regard as technology at all. Tarim shared a project in which the door of a dolls house had to slam shut at a particular moment in the theatre piece; the best solution was a stage manager tugging a length of invisible string at the perfect moment. Using the end goal – the effect that you are trying to create - as the starting point and then finding the simplest means of achieving that goal is perhaps a preferable method to starting with the a particular technology and then trying to incorporate its multiple functions into an artwork.

3. On the flip side, sometimes surprisingly complex technology embedded into a project can give the illusion of little or no technology. In A Knights Peril, a project by Studio residents Splash & Ripple, medieval-looking ‘Echo Horns’ are given to the public to enable them to listen in to the secret stories hidden in the walls of Bodiam Castle. To retain the aesthetic and magic of the horns, Tarim developed a dual-board system that brought the horns to life when unplugged from their charge point, rather than requiring the use of a much simpler on/off switch that could have broken the magic of the experience.

4. When making artwork for the public things need to be robust. Tarim’s rule of thumb is that any object needs to survive being thrown down the stairs. One trick that Tarim recommended, is that if something is made to look really delicate then the public are likely to treat it with much more care (as they would a piece of art in a gallery or a museum exhibition).

5. Tarim’s final top tip is that maintenance is key to any public artwork. From the start of a project, if something is designed to be long lasting then there needs to be a strategy and budget in place to maintain it. Tarim shared a number of public (particularly kinetic) artworks from Bristol and beyond that opened with great fanfare around their interactivity, and now languish in their broken form as more emphasis was placed on the original commission, than the on-going maintenance and upkeep of the work.