Lunchtime talk write-up

Posted on Fri 17 Jun 2016

Designing the compassionate city: creating places where people thrive

Jenny Donovan is a Melbourne based urban designer and town planner. She advocates for cities to be places that nurture people to thrive and meet their full potential.

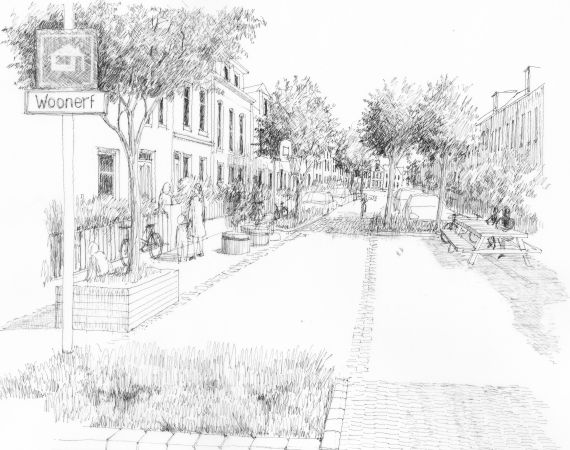

Image courtesy of Jenny Donovan

Jenny Donovan is a Melbourne based urban designer and town planner. Her central idea is that towns and cities are places that can nurture or stifle people, enabling people to thrive and fulfil their potential or consign them to diminished lives. She believes this is of profound importance and we all have a responsibility to be aware of the implications of our actions on the ability of other people to thrive. She further believes appropriate urban design is an important factor in creating places that best facilitate people to fulfil their potential: compassionate cities . Here are five things I learned about compassionate cities:

1. The relationship between people and place is complex and unique to each individual. When we build, manage, occupy, design or even pass through a place we change it and construct memories that affect our relationship with it. Jenny has observed a correlation between the socio-economic status of an area and the quality of investment in its urban design that reflects and reinforces the social gradient of health. More investment in design often means a place is more welcoming for people and provides an invitation for activities such as cycling, playing or walking. Places with lower design investment are likely to be less welcoming and offer less invitation for activity.

2. Jenny introduced a scale of happy and sad associations. For a community, a place is comprised of both a social and a physical landscape. The happy and sad associations of each place can be tipped according to memories and experiences that have been formed around a place. If a community is empowered by and feels a sense of ownership over a physical landscape, then a social landscape is likely to reflect this sense of achievement and empowerment. The extent to which people have a sense of hope or belief can be deeply rooted to the environment they inhabit and provides a catalyst for a sense of self fulfilment or in absence can be a major inhibitor to forming a sense of community.

3. A place will influence an individual’s ‘experience diet’ – what we choose to do or tolerate doing; including who we meet, what buildings we interact with, what we eat, and what inspires us. The design and make-up of our environment creates the potential to ensure that the things that meet our needs are preferable, not just possible. For example, if a city has accessible, attractive allotments or rooftop vegetable gardens, then people will have better access to fresh locally grown produce and may be more likely to teach their children about nutrition, or grow their own food.

4. Cities are made up of hardware (physical constructions), software (street furniture or more temporary structures) and orgware (policy, legislation and gatekeepers). All three elements interplay with each other to influence how nurturing or neglectful a place is for its inhabitants. Jenny believes the role of an urban designer is to empower communities to have a voice and a responsibility for the way their place is developed, to advocate for change and plan for the future.

5. Jenny works with communities to design spaces that work for them. The emphasis is on the social benefit of any change, looking beyond the design output. Jenny worked with a number of local communities in Palestine on Placemaking projects to repurpose unused spaces and reconnect the community with the places they inhabit. Focusing on the community priorities, stakeholder approval and implementing partner support enabled the project to consider the importance of emotional capital rather than financial return. The client (UN Habitat) post construction assessment suggests that designing for compassionate cities can positively impact on health, achievement and sense of belonging in a place.