Studio blog

Posted on Thu 21 Jan 2021

Future Themes Blog - The (Future) Wales Coast Path: Conversations

In the first of our Future Theme Blogs we hear from Resident Alison Neighbour & her team. Last year the Studio funded seven teams of Residents to explore ideas at the intersection of technology and culture.

Credit: Chris Lloyd

We begin with a flood map, showing the areas of Wales at risk of tidal inundation, and a 2019 newspaper article about Wales’ first climate refugees that announced to a small coastal village that their homes were now worthless. We recall half-remembered pictures on the television news from devastating floods in Bangladesh a decade earlier, floods that are becoming part of day to day life there.

We’ve known about rising sea levels for a long time, but oddly we don’t talk about the impact of them that much, not in the UK anyway. The (Future) Wales Coast Path is about acknowledging loss and stimulating conversation about how we could adapt, it’s about finding a way to begin that conversation by forming a connection with another part of the world that has more experience than we do here, and inviting audiences to engage physically with the space that will be lost and everything held within it. It’s a lighthouse, a walk, and maybe in the future it’s also an audio guide and a book.

Sea Wall rising tides, Gwent Levels Credit: Alison Neighbour

The lighthouse sits on the (future) coast path of Wales, a few miles inland on the Gwent Levels, on the edge of the village of Magor. It is connected via the magic of global data systems to a town in Bangladesh called Chittagong, a port city on the eastern edge of the Bay of Bengal, opposite the mouth of the Meghna river and on a latitude with the Sundarban region. When the tide rises in Chittagong, the lighthouse in Wales flashes a warning to alert us to the risks the Bay of Bengal faces imminently from sea level rise, and to remind us that the storm will come to us in Wales too.

The Lighthouse, designer Alison Neighbour, Credit: Chris Lloyd

The idea of this lighthouse came from a desire to sound the alarm, to start a conversation, to connect people to think about how we can adapt to the future. I wanted to physicalise this idea of impermanent land in the landscape itself, so that it can be felt in a way that a map or a newspaper article can’t offer. It is intended as a point of convergence, a place for encounter, and a site of pilgrimage, from the past shoreline to the future. We can walk together between past and future coastlines, feeling the distance of that journey and the life held within it, and come together at this place to be reminded of the need to adapt and plan for a different future. In time, I hope the journey may be accompanied by the sounds and voices of other people who have already been on this journey in other places and other times. The idea of conversation is crucial - climate crisis is not something we can deal with alone, it’s difficult, it’s frightening, it’s hard to know what’s best to do - we need each other so that we continue to be challenged to do better, and so that we can put our heads together to find solutions and empathy.

No Room created by Vikram Iyengar

For the past few months, I’ve been privileged to collaborate with artists Vikram Iyengar and Ken Eklund, to question how we might integrate those voices across time and place, and how we can create connections between audiences so that the lighthouse becomes a place where they can meet and choose a forward path together.

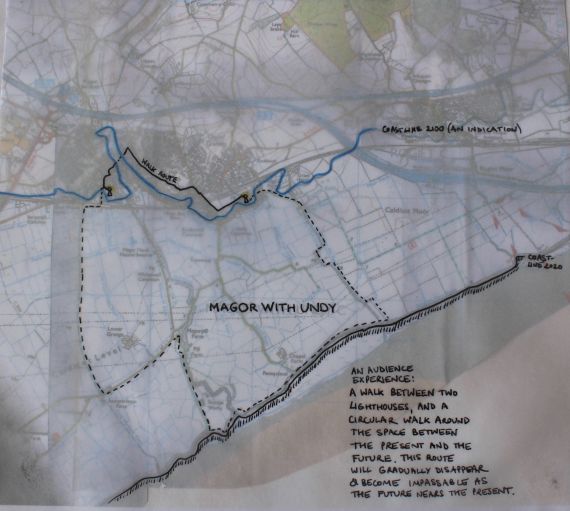

The Walk Created by Alison Neighbour

We went on many journeys of exchange together, meeting the challenges of time zones and the climatic and political situations in each of our homelands, and we’ve created a map of the paths we took which you can look at here. We hope you’ll enjoy exploring them. Both Ken and Vikram have written their personal reflections on our work together below - We did not solve all the problems we set out to solve, in fact we have as many questions as we have answers, but we’d like to invite you, the reader, to join us now on this journey.

-Alison Neighbour

-----------------------------------

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time... Known, not known, because not looked for

But heard, half-heard, in the stillness

Between two waves of the sea. “ ― T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets

My exploration of this project began at the path, which led to the lighthouse; and I returned again and again to this path, but it was not the same path; and many times I again passed the lighthouse, but not the same lighthouse. I was trying to know these places for the first time.

As a game designer, I try to keep the “player” always in mind – in this case, the player is the person who will walk the (Future) Wales Coast Path and stand before the lighthouse; who will interact with them in some way; who will bring something to the work and take something away. Who is that person and how do we connect with them? How do we start a conversation? Especially one that stays with us, and does not slide away like a bad dream (as so many conversations about global warming and sea level rise seem to do).

Lighthouse image by Rhys Kentish via Unsplash

Let’s start with lighthouse, itself a symbol of withstanding, of communication and connection even in uncertain times and under dire weather. You have perhaps seen photos of lighthouses standing tall on the shoulder of the land, prevailing against storm tides, sending out their message of I am here, I am here. How strange it will be, then, to come across a lighthouse well away from the sea... whose beacon is saying, it is going – your land, the houses, they are going. Or, maybe: it is coming – the tide, the flood, it is coming.

Along the way I stumbled hard over hiraeth, a Welsh word akin to the Portuguese saudade: undefinable, but I might say “nostalgia for a place or moment that is gone and may never have actually existed” and you might feel what I mean. And then I sank up to my waist in the term “reclaimed land” – as though the sea had seized the land away from us and we humans had taken it back. What I heard then, as between two waves of the sea, was This was never yours. None of this is yours.

So now you can imagine: human lighthouses standing like pawns on the great chessboard of the world; and as the seas rise, humans on every shore playing chess with the sea. And with infinite slow sadness, the grandmaster our mother ocean will win every game. This is what I want to tell the player walking the path and standing before the lighthouse: this is not about a swath of land, or a foot or two of water; this is more than resistance and surrender; this path is every path, this lighthouse is every human endeavour, and the light is telling you, In time you too will inexorably return to the sea.

- Ken Eklund

-----------------------------------

Elemental Bodies 1

As a dancer and choreographer, I work primarily with movement, space and time. And – of course – the body. And stillness. I focus on the live occurrent ephemeral experience that is shared simultaneously by the artist and audience in the same time, space and place. What could I bring to an idea that did not essentially require this?

How does a body experience landscape? How do we talk to it, exist in it, allow it to talk to us and through us? How do our elemental bodies converse and commune with the elemental earth? And can simple, personal, embodied experiences of rhythms, silences, stillness, walks, (dis)balances help (re)connect audiences whom we may never meet to themselves and to us, to a landscape they are in and to a landscape they may never see? How do we convey that we are all on impermanent land, shaky ground – the lighthouse and all of us?

another we. Caption: waving goodbye from the precarious banks of a Sundarbans island. Image: Vicky Long, 2011

Who is all of us? We, at the lighthouse creating or experiencing a climate-related art project? Or another we in the Sundarbans with the climate crisis at our doorsteps, trying – without resources, without support, without a voice – to somehow live through the day, each day? And what right does the first have to even think of twinning with the second!

Elemental Bodies 2

The Sundarbans is the largest mangrove area in the world shared between India and Bangladesh. Fringed in the northern curve of the Bay of Bengal – a huge area of sea that is anything but a bay – this is home to the largest delta system in the world, made up by the three river systems of Ganga, Brahmaputra and Meghna. This vast tidal landscape may look peaceful, but it is unpredictable and dangerous. In the network of hundreds of rivers, the tide rises up to 30 feet twice a day, drowning and revealing islands in an inexorable movement as old as time. Mangroves with their specialised pneumatophores (breathing roots) are adapted to live in these conditions – but the balance in the ecology is extremely fragile. This is the home of the Royal Bengal Tiger, the King Cobra and the Gangetic Crocodile. It is also the home of millions of people who live in one of the most densely populated, poverty-stricken, and ecologically fragile areas on earth. People literally live on the edge.

mangroves and pneumatophores. Caption: Mangroves and Pneumatophores – holding life in place. Image: Vicky Long, 2011

Mangroves are nature's defence against the tides which travel 200 km inland, way past Calcutta. With their network of claw-like roots, mangroves hold the soil in place preventing erosion. But on island after island these magnificent trees have been replaced with defences of concrete, brick, sandbags, and more. And on island after island, these defences have been repeatedly breached by the unstoppable waters of the rivers and the sea. The only success stories have been from areas where mangroves have been replanted as collaborative efforts between local communities, environmental agencies, and governmental departments. But even as these survive and thrive, other islands disappear forever in the swirling and rising waters.

Breaches. Caption: devastation of a village on Sagar Island by repeated breaches. Image: Vicky Long, 2011

Elemental Bodies 3

The Sundarbans is a microcosm of the climate crisis in all its complexity. Rising sea-levels, soil salinity, increasing number and ferocity of cyclones, unplanned and unsustainable development, terrible infrastructure, man-animal conflict, dense human population, poverty and deprivation... the list goes on and on. And yet, it is one of the most awe-inspiring places that this planet has gifted us. It is unfathomable – the idea that this may be gone, swallowed up by the waters that gave birth to it in the first place, primarily because humankind has been unable and unwilling to learn to live with and within this ecology. But Calcutta will be swallowed up too – there is nothing to protect the city from the furies of the Bay of Bengal but the mangroves. Most recently, Cyclone Amphan demonstrated that clearly – it made landfall in the Sundarbans and then passed over Calcutta decimating much in its path. The destruction was tempered only because the mangroves that remain absorbed the first onslaught and slowed Amphan down. Nature is no longer giving us warning: she has – justifiably – declared war.

Amphan. Caption: 21 May 2020 – the day after Amphan from my balcony. Image: Vikram Iyengar, 2020

“Age teaches you to recognise the signs of death. You become aware of them slowly over a period of many, many years. The birds were vanishing, the fish were dwindling and from day to day the land was being reclaimed by the sea. What would it take to submerge the tide country? Not much – a miniscule change in the level of the sea would be enough” - Amitav Ghosh, The Hungry Tide

- Vikram Iyengar