Posted on Thu 26 May 2016

Day 2: The hacks

If you've been following the storify you have no doubt caught some intriguing snatches of what our hackers and musicians got up to. I've been catching up with each of them to find out a little more about their projects.

Posted by

Project

Hack The Quartet

A quartet is like a game of chess; simple in its make up and infinite in its possibility. So how can new technologies be used to augment performance of and engagement with chamber music?If you've been following the storify you have no doubt caught some intriguing snatches of what our hackers and musicians got up to. I've been catching up with each of them to find out a little more about their projects.

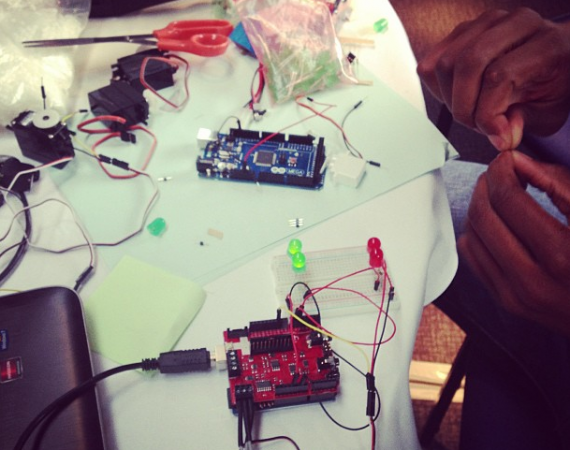

Silas Adekunle has been taking ECG readings using a biometrics kit and representing the outputs from the sensors visually through LEDs, and physically through a servo motor. I held the motor in my hand and felt the regular movement of the moving parts.

Silas Adekunle's Heart photo by Grace Denton

When he jogged his legs up and down the motor worked harder, suddenly agitated in response to his quickened heart-rate. Practically holding his heart in my hand was really emotive, and I imagine feeling and seeing the range of feedback throughout the quartet's performance would really allow access to the emotion and passion within the piece.

Heidi Hinder created 'Inside the Quartet' by inserting a lipstick camera where the tail piece of the violin would usually be. The resulting live images, fed onto a large LED TV from inside the body of the instrument, are quite stunning.

Heidi Hinder's Inside the Quartet photo by Heidi Hinder

As the Sacconi Quartet's instruments are so old and valuable Heidi could not experiment with those, but the next stage in developing the project would be to access much more advanced cameras and microphones which could be inserted with no detriment to the instrument or the way it is played.

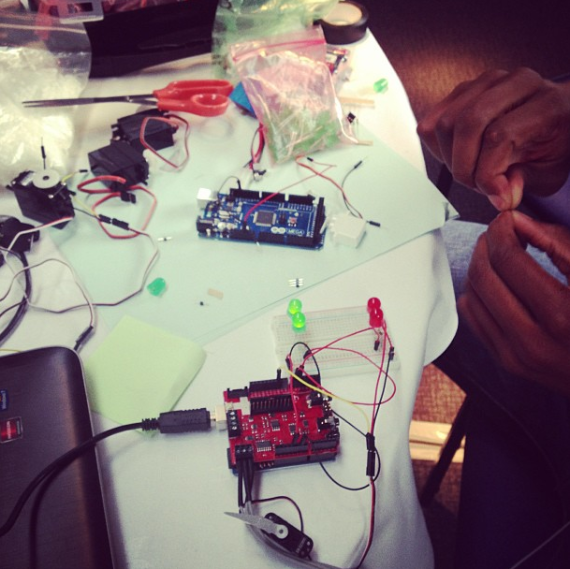

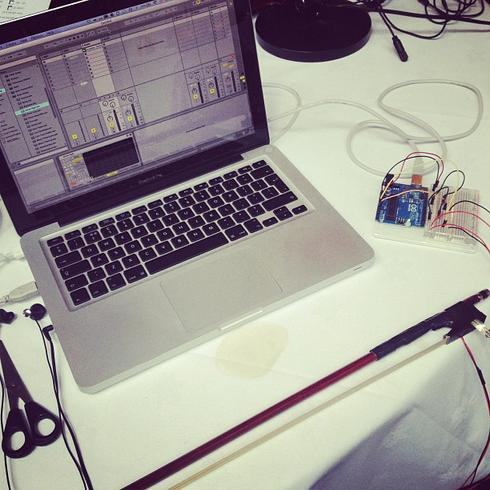

Liam Lacey created a force-sensitive bow by adding resistors to the places where most pressure is applied. The data from these resistors is sent to an arduino and translated into midi that can be used in music production software so the player can manipulate the music just by playing, bringing in effects and modifying the sound in different ways.

Liam Lacey's Hyperbow photo by Grace Denton

Laurel S. Pardue and Natasha Trotman collaborated on a number of ideas but the most workable hack they settled on involved visualising the musicians' breath as they play. Breath is something that binds the quartet together, it becomes a means of communicating and is integral to the music they create. The pair wished to involve the audience in the breathing to add to the rhythms and visuals already on display. They hacked a heart-rate monitor strap worn round the chest, adding conductive elastic to measure when the chest expanded and contracted with each breath. This data then affects the visuals, which look like small overlapping clouds that gather and disperse as the musicians breath in then out.

Laural Pardue and Natasha Trotman's Breath of the Quartet photo by Heidi Hinder

Peter Bennett worked with Matt Davenport to trial Phasetapper, a silent metronome that a musician can wear on any part of their body which taps a rhythm to play in time with. Each member of the quartet wears one of these devices and using MaxMSP Peter was able to control the rhythm of each metronome in relation to the others. By making them slide in and out of sync with each other he created a mexican wave effect of staggered music that falls in and out of sync. Simple but beautiful.

Peter Bennet and Matt Davenport's Phasetapper photo by Peter Bennett

Pete Redhead and Ollie Williams created the Barcconi Quartet, the best pun-name of the hack! This involved taking sound from a microphone into a laptop, analysing the frequency of this sound to find the notes being played, sending that data to an arduino which then hits the appropriate bottle (each filled with just enough water to tune it to a note on the scale) to play along with the music.

Pete Redhead and Ollie Williams' Barconni Quartet photo by Vannessa Bellaar Spruijt

James Leahy worked with Yann Seznec to create a score visualiser which analyses the music as it is played and opens up the scoring to those who can't read music. He developed a system that displays a different shape for each instrument which moves around the screen relative to the pitch and the octave the musician is playing. These characters also dance around staves which display the original notation, for those who can read it. The density of the shape denotes the volume of the note played to reflect teh dynamics of the piece. The next stage of the process is to add colour which would denote the timbre of the notes being played, and a history function which will mean that notes remain on the screen for five beats after they've been played.

A malfunction in the system resulted in a beautiful image

James Leahy's Live Score photo by James Leahy

Daniel Jones and Nick Ryan developed a system that samples a section of improvised music and produces a brand new score based on different factors within the music. The score that's generated is displayed on four iPads in real time, one for each member of the quartet to sight-read as it emerges. Seeing them play this experimental and completely new-sounding score was a very special moment in the hack. Daniel Jones has a full write up of the process on his blog.

Daniel Jones and Nick Ryan's generative score photo by Matt Davenport

Stefan Goodchild and Pete Fairhurst created an absolutely beautiful piece, using the recording of the quartet made the previous day. He programmed a set of light-based visuals to respond to different factors within the music, and projected these visuals through a room filled with smoke, creating volumetric shapes. Essentially, he created four tubes of light, one for each quartet member. Concentric circles within the tubes formed and rolled and dissapeared in response to the music. It's quite difficult to describe, but show-stopping to watch. Have a look here. I honestly could've stayed standing amongst the light for hours.

Stefan Goodchild's hack photo by Simon Moreton

Yann Seznec made a number of quick hacks. Firstly a game in which pulsating elliptic shapes in a virtual game environment represented each quartet member. The shapes vibrated according to the music each performer played. The player is free to approach and move away from each member of the virtual the quartet, listening in from different angles, the mix of sound varying accoring to how close/far you are from each violin, viola or cello. The player could jump up onto each member's virtual platform to listen to the piece from their point of view. He also made a beautiful device, adapted from a carved wooden antique-looking box, adorned with various buttons and switches. Pull a chord out of the side - much like a child's toy - to record and play back, in an altered way, 30 seconds of audio.

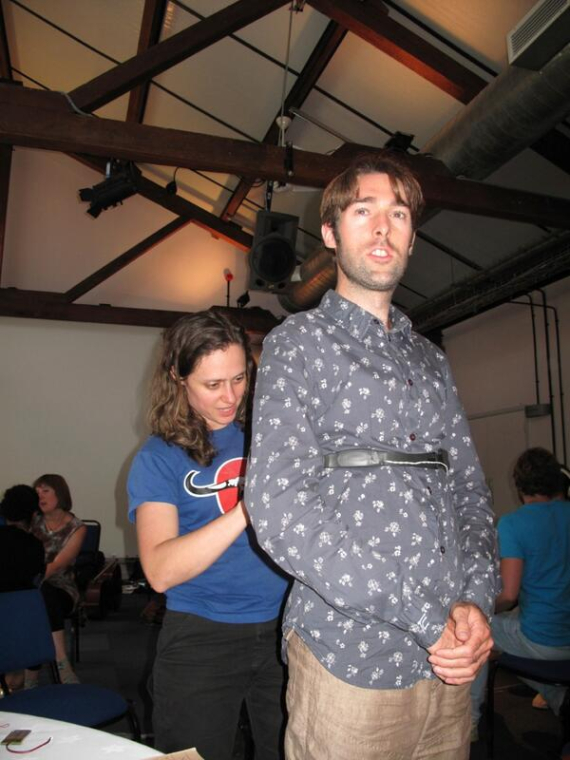

Ruth Farrar and Ana Tiquia worked together on Points of Audition, an app which allows remote listeners, those who are either financially or geographically prevented from attending concerts, to experience the quartet from many different viewpoints. Having strapped Go Pro cameras to the heads of each quartet member in turn they recorded the piece from all angles, both audio and visuals, so you can now experience the quartet's performance from their own view!

Ready to record for Points of Audition, with a go-pro camera strapped in place! photo by Cara Berridge

Sam Underwood concentrated on the lesser-heard sounds created by the live performers, the breathing, the creaking of chairs, the rustles and squeaks that may not have been intended but which can enhance the performance and create a new level of intrigue from sound art and experimental audiences. He created an installation which allowed you to experience two versions of a performance in one. Behind the performer, the breathing, page turns and rustles are amplified, move in front of the performer and you hear the more standard, instrument-led sounds. Sam laboriously recorded and amplified these sounds by using contact mics and close-miking techniques. He was interested in what audiences would do when given the option of listening to the traditional or more unusual soundscapes. During the final showcase he was delighted when one person chose to listen to each and then returned to the sounds of breathing etc to complete their experience.

Recording for Sam Underwood's One is Too photo by Heidi Hinder

Lee Nutbean worked with Ollie Williams to create Heartstrings, a hack which uses a heart-rate monitor to translate biofeedback into music by plucking the strings of a hacked violin in time with the musician's heartbeats. At the final showcase, two members of the Bristol Metropolitan Orchestra were hooked up to the device and played as the heart-reading robot plucked merrily in time with their own heart, the robot seemed to slip in and out of time with the music creating an extraordinary impression that there were three musicians involved.

A selection of the hacks on display for the showcase photo by Pete Fairhurst

The whole two days was an inspiring blur of ideas and mad-dash winging it. Some came with pre-planned ideas, while others made it up as they went along. Nothing was 100% developed because it wasn't supposed to be. But the range of hacks, enhancements and augmentations that came out of it is truly exciting.