Studio blog

Posted on Mon 14 Sep 2020

Mars, Earth, isolation and at home missions

Artists' Ella Good and Nicki Kent explore what a human future on Mars might feel like and what we can learn from our experiences of life in lockdown in 2020.

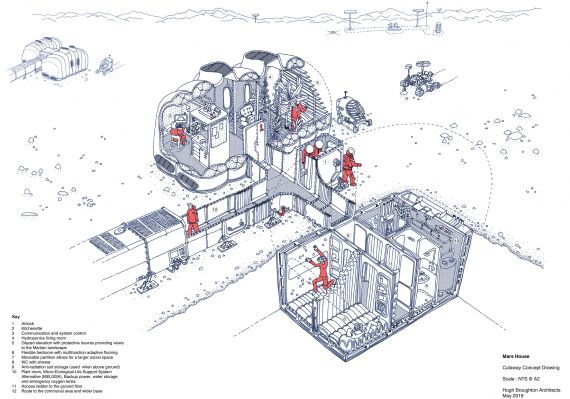

Concept design for Building A Martian House – base (Hugh Broughton Architects 2019)

Artists Ella Good and Nicki Kent are working with the people of Bristol towards Building a Martian House - a real life house that you can step into and imagine how we might live on another planet, in a very different climate. In the early part of this year they joined Watershed & MAYK's Winter Residency programme to explore what could happen inside of the house, a residency that was one of many things to be disrupted by the public health crisis. We decided to slow the end of residency until the autumn and are currently planning an exciting showcase to celebrate their thinking, details of which we will share soon.

In the meantime, we wanted to share Ella & Nicki's latest project blog post, exploring what a human future on Mars might feel like and what we can learn from our experiences of life in lockdown in 2020 ...

Mars, Earth, isolation and at home missions

Back in 2013 we met Alison Rigby. Alison was an astronaut hopeful, but unlike you’d expect she wasn’t an ex-fighter pilot training with NASA. She was a secondary school lab technician living in a small flat in London with her boyfriend and two ferrets.

Alison had answered a world-wide call out from a company called Mars One and applied to be one of the first people on Mars, for a mission that was planned to launch in 2023. Mars One looks unlikely to be making the trip and most in the scientific community have discredited their plans, but in 2013 the mission felt (as far-fetched as it may seem) a possibility. This was the first event that really sparked our interest in Mars and began our subsequent series of works.

Open calls for astronauts have happened before. Helen Sharman, the first Briton in space, applied to become an astronaut after hearing an advert on the radio, whilst she worked in a chocolate factory. Knowing this we weren’t phased by Alison’s small flat, as we sipped cups of tea and spoke about wanting to move to Mars.

Shortly after applying Alison decided to do a practice mission in her own home. Without anyone watching or studying the outcome, she bought all the food she’d need for two weeks and locked herself indoors. Then for the next two weeks she and her boyfriend didn’t leave the flat.

When we met Alison she told us about her Mars analogue mission in her living room. It felt like a hard, weird thing to do. She said what you’d expect to hear about the experience. It was kind of monotonous and a bit lonely. Alison was into gaming and didn’t mind spending lots of time indoors, but even for her it was harder than she expected it would be.

Since meeting Alison we’ve researched and spoken to other people that have practiced here on Earth for life on Mars. One of these was Andrzej Stewart (see our interview with him here) – an ex-military pilot who spent a year living in isolation in a small crew in NASAs HI-SEAS mission in Hawaii. A year spent on the side of a volcano, in a rocky Mars like landscape, whilst following strict isolation conditions, including a delay in real time communications with the outside world. There are lots of examples of these experiments around the world that show the only way to get to Mars is to practice here on Earth, and one of the hardest things about it is the isolation and sense of being confined; both to a small indoor space and confined to social interaction with just a very small group of people. The engineering and practical considerations can be prepared and accounted for, but the hardest thing is to predict how people will react to being cut off, away from everyone you know, unable to go outside and with Earth as a tiny speck in the night sky. I guess I’m telling you this because Alison’s at home Mars mission may seem strange but does have some correlation to what Space Agencies and scientists are doing as well.

Recently I’ve been thinking about Alison’s mission. We’ve all just had a bit of time where we’ve had to stay indoors a bit more than we’d like. Cut off from our families and friends with the option of a video call to keep up.

Over the last few years we’ve been asking people what they’d like their house to be like if they lived on Mars, for our Building A Martian House project. In all the workshops and events about this that we’ve run, people have often compared the idea of living on Mars to adventuring on Earth, to long distance boat races and serving in the military. Suddenly now, we all have a much more everyday experience of separation and isolation to refer to.

How can designing for Mars help us to consider what we’ve learnt from our experiences of life in lockdown in 2020? What became important? What do we wish we could change?

For me I’ve been thinking about what the implications of less real life social interaction or community might be. We already live in a world of disconnection, where shared physicality has been dwindling over recent generations – less children play together outside, things are delivered to us, less people know their neighbours. In one sense the urge to still connect with others is alive and well and certainly even heightened under lockdown, but in another it now doesn’t seem so much like the setting of a science fiction film to live in a world where everyone is home alone but connected digitally or virtually.

Is this vision of the future an extension of what we understand human progress to be? An essay I read at the beginning of lockdown by Charles Eisenstein asked: Does human advancement mean separation? Me separate from you, humans separate from nature. Is this the future?

Relatively early on in our design process for Building A Martian House, we ran a workshop with academics at the University of Bristol. One was a psychologist who had studied the psychology of people living in submarines. In our workshop she spoke about how our original plan to design a house for two people on Mars just wouldn’t work; the mental health of the people living there would deteriorate. We need more people around us, we need to be part of a community. This led us to design our house attached to a larger base – a small community of around 50 people, with a central village hall type space in the middle. This was the only way we were going to begin to address the mental health of people living there. We started thinking more about how we live together and how we can live well. The project became a context to consider what we value most about home life and community life.

We are only going to be able to build one of the houses in this community. But what happens in the new imagined village hall is still to be decided. Will there be events to bring people together? What might these be? Will there be a barn dance with Mars gravity? Celebration days? A hack space where people share the invention of new objects made from waste?

Concept design for Building A Martian House by Hugh Broughton Architects

Right now it feels a bit impossible to imagine a future where people can join together but hopefully the last few months have been a reminder of how important that is. We could have all slipped into our smartphones and laptops, or we could embrace opportunities to connect in person when we are able to. Looking back now it doesn’t surprise me that Alison didn’t enjoy spending two weeks with only one other person to speak face to face with. On week 3 of lockdown I spent an entire evening talking to my neighbour across the fence. This is an experience that has been repeated around the world – people talking across balconies, across fences, gardens. When we have to shut out the rest of the city, people living close by become important connections. Nowadays we’re used to feeling more part of a global community, more connected with issues around the world but usually less with life in your local area.

Our work as artists has always been about meeting people like Alison. Hearing other people’s views on the world and building a response that continues the conversation. Art as community making. Life is community. How can we find ways through events that rip through our normal routines and habits, to help us reimagine a future that we want to live in?