Posted on Thu 26 May 2016

Music and the Brain

Part of my ongoing research and interests are about unravelling the mysteries of why music has such a profound affect on the brain and memory and why our appreciation for music stays intact to the very end of our lives. How can playing particular songs to people with dementia evoke such strong…

Posted by

Project

Music Memory Box

Music Memory Box harnesses the evocative power of music to create a tool for people living with dementia to recollect, reminisce and reconnect with loved ones.Part of my ongoing research and interests are about unravelling the mysteries of why music has such a profound affect on the brain and memory and why our appreciation for music stays intact to the very end of our lives. How can playing particular songs to people with dementia evoke such strong emotions and revive lost memories?

I personally became aware of this ‘phenomenon’ with my own Great Gran – Winnie. I remember visiting her in a care home, and her not being able to remember who I was, she thought I was her nurse. I also remember her being confused about where she was; old stories, dreams and the present were intermingled into her everyday life. However when she was sat down next to a piano, she could play both hands to almost all the hymns in a hymn book, favourite tunes she had always played, like Country Gardens by Percy Grainger and also sing most of the lyrics too. I found it strange at this time that music memory stayed, whilst everything else had deteriorated. And the emotions she had always connected with these songs were evoked.

This is Winnie around her 100th Birthday:

When we are in our mother’s womb, this is our first introduction to music; our mothers’ heart beat providing a constant rhythm. The musical parts of the brain are developed before the language parts. We treat babies as musical beings by cooing to them, before language develops. This deeply wired understanding of rhythm and music might be why at the later stages of our lives we react to music so well.

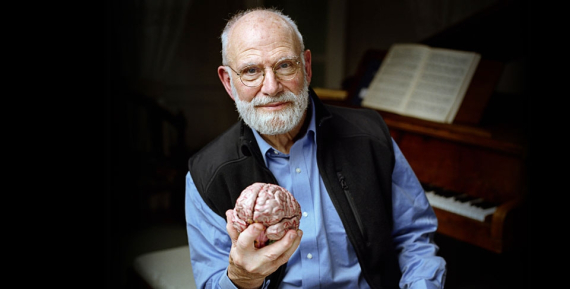

Oliver Sacks is a huge hero of mine, he combines my interests in people, science, the brain and music in one. He is a neurologist, amateur musician and he has devoted his life to understanding the brain and in particular memory and music. He writes accounts of his meetings with particular people in his startling books.

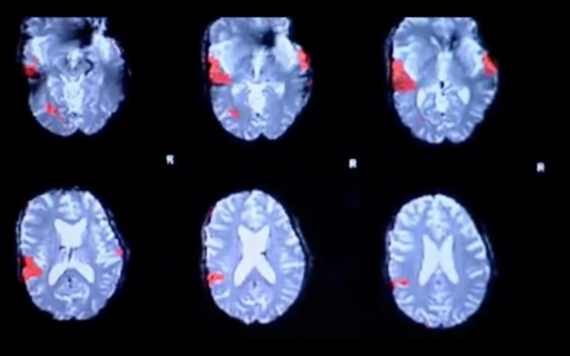

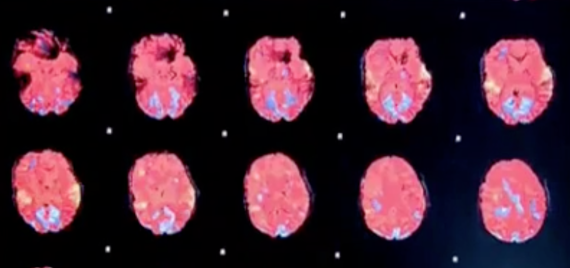

Alan Yentob’s documentary “Oliver Sacks: tales of Music and the Brain,” is truly remarkable. The documentary provides an interesting look at Oliver Sack’s history and we get to see many of the exceptional people he has met and case histories he has studied over the years. In a part of the documentary Alan Yentob offers himself up as a candidate for research to see how music affects the brain. He is asked to provide neuroscientists at the University of Sheffield with three different types of music. The first is a piece of music that makes him happy, the second is a piece that annoys or angers him and the last is a piece that he has a strong emotional connection to, something that moves him. The researchers use an MRI scanner to pinpoint the brains activity as the various pieces of music are played. The results are outstanding, the first two scans for the happy and angry music are similar, with little brain activity. But the last piece of music, a piece by Strauss sung by Jessie Norman, has a startling affect on Yentobs’ brain. His whole brain is alive, flooded and bathed in blood because he has had such an intense emotional response to it.

Alan Yentob's brain scan when listening to music that angers or annoys him:

Alan Yentob's brain scan when listening to music he has a strong emotional connection to:

Deeply personal music works well as a memory retrieval device; these are the paricular songs I am aiming to collect and collate for people when making the communal music memory boxes. Through various music workshops I hope to pinpoint songs that have particular emotional and immersing experiences for that particular person.

I have done my first music workshop with around twenty-five people from Falmouth Day Centre run by Age UK. Firstly my method is selecting a wide range of different styles and eras of songs people might like and then start funnelling each person’s interests and stories down. My first workshop went well. We listened to a few Cornish folk songs that got people singing along, and doing some actions along with the words, some songs were hits, some were not. Various songs and eras sparked dancing from people that have trouble walking, people were smiling, but also crying. I have a list of new songs to acquire for particular people for my next session. Once the song is set for each person, next each person can use a modelling material to make small representations of objects that relate to that particular memory/ story, to strengthen the memory trigger. I am also working with people that are blind, so I am thinking about how the textures of the objects and memories are just as important as the music.

Research states that the memory is spared for familiar music in Alzheimer’s Disease patients (Cuddy and Duffin 2005) and that the Medial Prefrontal Cortex, the part of the brain just behind the forehead, is the least affected by Alzheimer’s Disease and acts as a hub associating music and memories when we experience emotionally salient episodic memories that are triggered by familiar songs from our personal past (Petr Janata 2009)

For more updates @ChloeMeineck