The Afrofuturist melting pot

Posted on Thu 2 Oct 2014

Our Afrofuturism season launches into space this week. It has been curated by Dr Edson Burton, who has kindly written this article on Afrofuturism’s influences and influencers, inspirations and ideas – including his own personal journey.

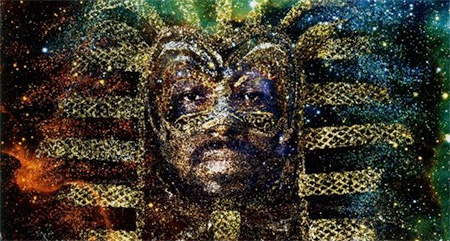

A place where space, pyramids, funk and politics collide, Afrofuturism is one of the most imaginative ways of re-defining and re-imagining black identity in the past, present, and the future. Launching into space this week, it's the first in our series of Sci Fi: Days of Fear and Wonder events, and is a diverse programme, for a diverse audience. It has been curated by Dr Edson Burton, who has kindly written this article on Afrofuturism's influences and influencers, inspirations and ideas - including his own personal journey. Thank you to Edson for a brilliant insight into his process, and for a fantastic programme of events - hope to see you all on the Mothership this month.

Dreaming of a world and dimensions beyond our own is a timeless and universal concern. But for people of African descent this musing has additional poignancy.

Exiled, enslaved colonised - how many Africans looked up at the night sky and pondered if there was another, kinder, world above in that great expanse? This yearning has been the inspiration of what today we term Afrofuturism, first coined by writer and critic Mark Dery in 1993 to capture the essence of what has become a discernible movement in African Diaspora art, music, film and literature.

A melting pot of influences

Curator Zoe Whitely describes Afrofuturism as 'a melting pot of Sci-Fi, fantasy, magical realism and Black nationalism". Using this culinary metaphor the earliest ingredients of Afrofuturism can be traced to the speculative fiction of African American writer Charles W Chesnutt (1858-1932) and scholar and activist W.E. Dubois (1868-1963). Both wrote Black speculative fiction which imagined future worlds and scenarios vastly different from the dystopias inhabited by Black men and women across the globe.

They were the most notable names in a literary tradition which included pulp and 'serious writers' - Black sci-fi truly came of age as a distinctive voice through the work of award-winning writers Samuel Delaney (1942-), Octavia Butler (1947- 2006) and more recently Nnamdi Okrafor.

Music - bringing all colours under one groove

Music, however, is the most pronounced flavour in the Afrofuturist melting pot. Avante garde free jazz musician Sun Ra (1914 -1993) is a cornerstone of the artistic development of the movement.

Born in segregated Birmingham Alabama, Herman Blount was rebirthed as Sun Ra in the 1950s after, in his description, a visionary trip to Saturn. Sun Ra's fusion of African spirituality and aesthetic set a blueprint for generations of Black musicians in particular the P-Funk pioneer George Clinton. Metaphors of flight and escape were reinterpreted in Clinton's universe: The Mothership was a benign vessel compared to the slave ships that carried Africans across the ocean. Funk was a universally harmonising influence - African-American in origin but bringing all colours under one groove.

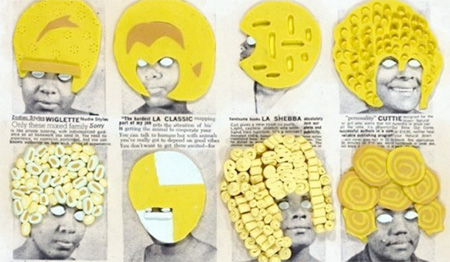

It is worth dwelling on this point. 1970s Black nationalism, from which Clinton emerged, was defiant, sometimes essentialising, sometimes exclusive. Black Pride made possible the Black hero(ine) - think Shaft, Jackie Brown, the Black Panther -but also raised the vexed question 'Are you Black Enough?'. Afrofuturism's pioneers, by contrast, have celebrated Blackness but have also subverted definitions of identity, race, gender and sexuality. Tradition is the launch pad - or rather the DNA - for new exploration.

Artist and scholar Denenge Akpem also uses Afrofuturism as a way of pointing to healing the scars of the Black past. Denenge synthesises the ritual traditions of African spirituality to create new forms of cleansing for future generations. Her work is typical of many Afrofuturist artists in that traditional cultural practice is integral to reimagining the future: you need to look forward to look backwards.

Music has been a vehicle for the cross art expression of Afrofuturism. From Sun Ra to Outkast and Janelle Monae via Earth Wind and Fire, Labelle, & Grace Jones, album cover art, futuristic fashion and far out stage sets articulate a shared vision of future thinking and future longing.

A glance at the costumes of the first generation of rappers including Grandmaster Flash, Afrika Bambataa and Kool Mo Dee reveal the influence of Sun Ra and Clinton. Hip hop is but one form of Black electronic music inspired by future visions. Genre hopping DJ King Britt, deep house maestro Osunlade, Flying Lotus, drum and bass pioneer Goldie, and Bristol's very own trip hopper King Tricky are just a few artists whose work falls within the framework of Afrofuturism.

Afrofuturism on screen

The Son of Ingagi (1940) was the first Black sci-fi movie on screen. But from the 1970s onwards film became a vital ingredient in this Afrofuturist melting pot. Sun Ra and Clinton provided filmmakers with an entry to this 'new' and curious world. Sci-Fi offered the opportunity to imagine a yet unachieved resistance such as the Feminist inspired Born in Flames (1983) or a satire on racial politics such as Brother from Another Planet (1984) or later Cosmic Slop (1994). Real life and comic book characters inspired filmmakers to create their own heroes such as Meteor Man (1993) or to translate heroes from the comic to the screen such as Blade (1998), or Hancock (2008).

More recently filmmakers have pushed the boundaries of their visions through the short form. Robots of Brixton by Kibwe Tavres offers an intriguing slant on contemporary events. Wanuri Kahiu's striking post apocalyptic short Pumzi is a striking example of the vitality of the Afro Futurism scene on the continent, while in Touch Shola Amo presents an intriguing take on race and objectification.

As you can gather the ingredients for the melting pot that is Afrofuturism is no longer confined to the US. Artists from the African continent and from Europe, including Britain, are significant contributors to the scene.

Afrofuturism's Others, an exhibition which launched in June 2013, evidences the growing mainstream awareness of the scene in the UK. Wanechi Mutu, Ellen Gallagher, Layla Ali, Joseph William and Hebru Brantley are but a few artists whose work garners critical mainstream attention.

Afrofuturism at Watershed

Watershed's Afrofuturism season will introduce you to the pioneering films and personalities that have shaped the movement. In fitting celebration of Sun Ra's centenary we start the season on Thu 2 Oct with Sun Ra: A Joyful Noise, a documentary exploring his life and work. Later in the month we will come back to Sun Ra for Space is the Place (Thu 23 Oct).

Continuing with a musical theme discover the inner workings of Clinton and his collaborators in Tales of Dr Funkenstein (Sun 5 Oct). If you want to know more about the literary world of Black Sci-Fi then I recommend you check out the documentary Black Sci-Fi (Wed 15 Oct), and there's a chance to see the shorts I have mentioned and more in Visions of The Future: African Science Fiction Shorts (Sun 26 Oct). John Akomfrah's Last Angel of History (Mon 27 Oct) is a celebration of the work of the Black Audio Film Collective which today we recognise as a key influence on Afrofuturist artists. Check out the full programme at watershed.co.uk/afrofuturism - there's a whole world out there for you to discover.

As a curator, it is impossible to cover every aspect of Afrofuturism - the movement is so broad and so rich - but to introduce the context of the films many of our screenings will be supported by intros and Q&As featuring artists, filmmakers and commentators directly involved in the movement. If 21st Century technology does not fail us then we'll be joined live from Chicago by some the leading voices of the movement at the first screening on Thursday.

My Journey My Inspiration

For me this season is a voyage of recovery. I say recovery in the sense that many of my influences - creative and otherwise - have come from the sci-fi and fantasy worlds. As a child pocket money meant buying the latest X-Men, Luke Cage or Black Panther comics. Downtime in adolescence was spent reading pulp westerns or the Barbarian worlds depicted by Robert E Howard. My interest waned as I grew older as I struggled to ignore the limitations of my Black comic heroes and became frustrated by the racism of the pulp fiction writers I read so voraciously. Sci-Fi and fantasy still held my interest, though - like anyone else I dug Stars Wars, ET, Predator and Alien, but at one step removed.

My discovery of Afrofuturism brought back my connection to the world of Sci-Fi but also brought my interest in Black history and culture into a coherent world view. History and future could now reach back and forth in one glistening web.

It has inspired me to write - parables, utopias, fantasies, allegories - in short, to dream. I would like to share my inspirations with you.

Dr Edson Burton (Curator)