Mark Cosgrove Cinema Curator

on Thu 22 July 20211971: The Year Hollywood Went Independent

Posted on Thu 22 July 2021

Mark Cosgrove (Cinema Rediscovered Co-Founder) shares insights into how 1971: The Year Hollywood Went Independent came about and how that period relates to mainstream film culture today.

The 1971: The Year Hollywood Went Independent season came about through a number of routes. A couple of which are more interesting than the others. The less interesting but no less necessary perhaps: when putting a programme together - whether the focus is on a director or thematic - you always have in the back of your mind “what is the relevance, what is the hook?” Anniversaries give the most obvious hook; centenaries are the biggie, fiftieth is significant, decades can work…; what they mean though – beyond realising how old you are – can be debated. This however was not my rationale for looking at Hollywood in 1971 but rather a happy coincidence.

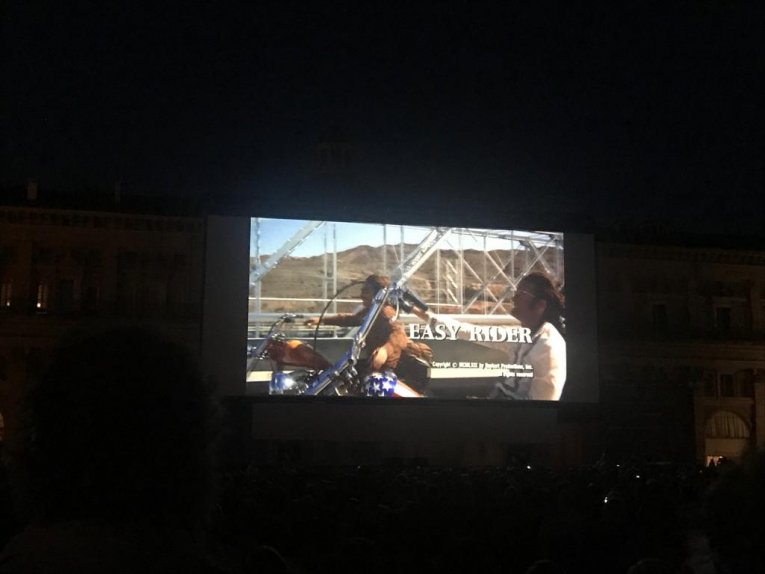

A couple of years ago, I saw the restoration of Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda’s era defining, ground breaking Easy Rider (1969) at Il Cinema Ritrovato in the dramatic outdoor setting of the Piazza Maggiore. It is a film I am very familiar with but was struck on seeing it on such a scale at how visually experimental it is, in terms of shot composition and editing. Biker movies were a familiar genre in the 60’s aimed at the disgruntled youth and counterculture market building on the success of 50’s films like The Wild One (1953) (“What you rebelling against, Johnny?” “what ya got ?”) and Rebel Without a Cause (1955). This youth market was nurtured by that industrious and opportunistic film producer Roger Corman (what else can a good producer be but opportunistic and industrious?) who could instinctively smell and exploit an evolving market trend.

Easy Rider (1968) screening at Il Cinema Ritrovato on the Piazza Maggiore in Bologna. Photo courtesy of Mark Cosgrove.

Easy Rider (1968) screening at Il Cinema Ritrovato on the Piazza Maggiore in Bologna. Photo courtesy of Mark Cosgrove.

But it was the commercial success of Easy Rider which focussed the mind and attention of the Hollywood studios who were drawn to the scale of its box-office success and importantly its profit margin – made for under $500,000 it would end up taking $60m worldwide. By the mid-sixties, the studios were well into their own existential contortions with declining cinema admissions as television took audiences’ attention and a wealthier middle-class migrated to the suburbs and away from the city centres where the majority of cinemas were. Into the bargain Hollywood’s epic productions – their response to the challenge of television – were expensive to make and were not turning a profit e.g. Dr Dolittle (1967) made for $17m took barely $9m at the box-office.

They opened the door to the the Easy Rider talent with a view to reaching this new counterculture audience and of course replicating the profit margin. That pool of talent was largely made up of the alumnus of the Roger Corman school of “make them anyway you want as long as they are cheap.” This was an extended group around the then unknown Jack Nicholson which included director Monte Hellman, writers Terry Southern and Carole Eastman, who all had interests beyond the mainstream of American culture. Hellman for example had done an early American production of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, Terry Southern was part of the Beat scene in Greenwich Village.

The wider context, beyond the increasingly irrelevant stories coming out of Hollywood (Dr Dolittle anyone ?), was a world in general and an America in particular going through profound social and political upheavals which still resonate today: a generation was taking Dr Leary’s psychedelically informed advice to “turn on, tune in, drop out”; civil rights protests at home was seeing some of the worst state sanctioned violence on its own largely Black citizens; Martin Luther King’s assassination followed tragically on the heels of those of John F. Kennedy Robert Kennedy and Malcolm X; the Vietnam war was increasingly coming to dominate the headlines and was being brought direct into people’s home via television; Richard Nixon and Watergate were just round the corner. The American psyche was in freefall.

Amidst this tumult, to survive financially, Hollywood needed to reconnect with a new audience that its now ageing studio heads, shaped in the heyday of the classic era of the 30’s and 40’s, had little to no understanding of. The times were indeed changing. The economic logic meant that they somewhat reluctantly hitched their immediate future to a ride with the anti-authoritarian counterculture biker duo Captain America and Billy who would take them and the audience through previously unseen landscapes.

This new Hollywood – or American New Wave as it became known – would last until the equally surprising twin box-office successes of Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) created commercial models which Hollywood could understand: the summer blockbuster and the franchise. In those seven or eight years, the Hollywood studio system produced some of the most startlingly original cinema made by a young generation of filmmakers and writers who were more influenced stylistically and thematically by the new European style of the likes of Antonioni, Bergman, Fellini and Godard than they were by traditional Hollywood genre films. And to this cinema curator at least, 1971 was a high-water mark with films like The Last Picture Show, Klute, Five Easy Pieces, McCabe & Mrs Miller, Two Lane Blacktop being released in the US and the UK.

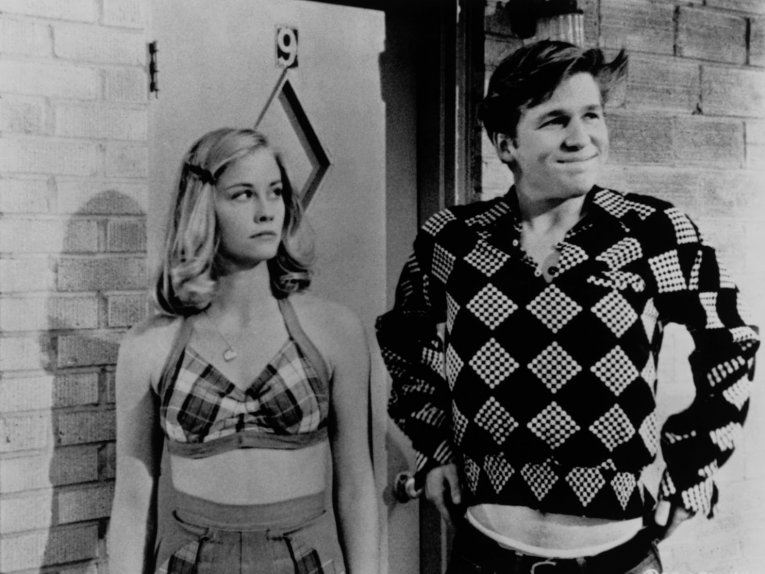

The Last Picture Show (1971)

I could have picked more than the five films presented here but due to COVID restrictions, cinema space is at a premium. This, however made me focus on the essential. These five films represent an exploration of the existential state of the American psyche in this tumultuous period – whether it is through the radical framing of Klute’s cinematographer Gordon Willis, the terminal ending of Monte Hellman’s Two Lane Blacktop or the uncertain future of The Last Picture Show’s young protagonists. I wanted to resist those films which were more about a grittier updating of existing genres e.g. The French Connection and Dirty Harry but focus on the more uniquely personal style of filmmaking that Hollywood allowed at this time. It could be argued that McCabe & Mrs Miller is nothing if not a grittier update on the Western; but Altman’s confrontational approach to cinematography and sound keeps the audience away from any easy genre thrills.

A big omission however is Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song which unlike Gordon Parks’ Shaft (also released in 1971) is formally a more adventurous blaxploitation genre origin story. Prosaically, it is not available to screen theatrically in the UK…; such are the challenges of theatrical rights and cinema curation. However, I was delighted by the serendipity of Cinema Rediscovered being offered the UK premiere of the restoration of Melvin Van Peebles’ debut feature The Story of The Three Day Pass by Janus Films. This striking feature made in Paris in 1967 gives full evidence to the influence of the formally radical approach of the Nouvelle Vague – jump cuts, direct address to audience – which would be more widely seen in Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song. So as well as this being the first time The Story of The Three Day Pass has ever been screened in the UK, it must also stand in for this most annoying of omissions. As an aside, the circumstances of the making of The Story of The Three Day Pass only enhances the respect due to and reputation of the already phenomenal creative force that is Melvin Van Peebles.

The other context to marking 1971 and framing it between Easy Rider and Jaws / Star Wars is that this period on the New Hollywood has most popularly been defined by the all-male brigade of auteurs from Coppola to Scorsese. I wanted to draw attention to the female stories from Jane Fonda (Klute) and Julie Christie (McCabe and Mrs Miller) radical reworking of female representation onscreen to reminding new audiences of the on-screen talents of Cloris Leachman who won best supporting actress for her performance in The Last Picture Show (and who sadly died early this year) but also to the behind the scenes creative contributions from the likes of Polly Platt - who many argue was the true creative force behind The Last Picture Show, and the extraordinary writing of Carole Eastman who perfectly captures male ennui in Five Easy Pieces, as well as writing a career defining scene for her friend Jack Nicholson. Thanks to Invisible Women for diving deeper into this area and surfacing more of the contributions from women to this creative moment (read: Invisible Women of 1970s Hollywood and join in free online event Rewriting Film History (With The Women in it) on Fri 30 July 3.30pm.)

Mccabe & Mrs Miller (1971) Photo courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures

As I said at the beginning, the seed of the idea started by that re-watching of Easy Rider in June 2019, it was nurtured by re-reading Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock 'n Roll Generation Saved Hollywood, J Hoberman’s The Dream Life: Movies, Media and the Mythology of the Sixties and by delving into my back catalogue of the critical film journal MOVIE. It was brought into contemporary focus by reading Martin Scorsese’s essay in Harper’s Magazine Il Maestro: Fellini and the Lost Magic of Cinema (March 2021) where he reflects on the influence of the franchise and streaming companies on cinema in general and the kinds of stories Hollywood allows itself to tell.

Scorsese, along with his long-time collaborator editor Thelma Schoonmaker were beneficiaries of the creative freedoms afforded filmmakers in this period with, for example, Taxi Driver (1976) made through Columbia Tri-star. Unlike some of the directors in this season – Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafelson and Monte Hellman – Scorsese managed to navigate a personal filmmaking within the increasing commercial pressures of the 80’s, 90’s and beyond. Scorsese is of course an established critically acclaimed filmmaker with a prestigious filmography but the irony will not be lost that Hollywood would not take the risk to finance The Irishman (2019); it was a streaming platform which allowed him to make one of his most personal projects. At the same time, much was being made in the trade press of Chloé Zhao, director of exquisitely crafted independent films of American outsiders The Rider (2017) and Nomadland (2020), going to Hollywood to make Eternals, the latest in the Marvel Cinematic Universe franchise. Will she be able to make the film she wants to make or the film the studio wants her to make? Or will this give her - and others from the independent filmmaking world who are now courted by Hollywood - the space in the mainstream to make the kind of intimate stories of a marginalised America and a personal filmmaking that enriches film culture?

Finally, the season came to fruition by revisiting the films and being reminded of their adventurous, defiantly independent, cinematic storytelling.

Presented by Cinema Rediscovered and Park Circus, the 1971: The Year Hollywood Went Independent season launches at Watershed (Thu 29 – Sat 31 July) as part of Cinema Rediscovered and tours to venues across the UK from Aug – Oct including:

- ICA, London

- Phoenix, Leicester (1 – 22 Sept)

- HOME, Manchester (26, 28, 29 Sept)

- Glasgow Film Theatre

- Broadway, Nottingham

- Chapter, Cardiff

- Showroom, Sheffield

- QFT, Belfast (6 Oct – 7 Nov)

- Filmhouse, Edinburgh

- Eden Court, Inverness

- DCA, Dundee

- Ipswich Film Theatre (19 Aug – 16 Sept)

- More venues to be confirmed