Mark Cosgrove Cinema Curator

on Mon 18 July 2022When Europe Made Hollywood: From Sunrise to High Noon

Posted on Mon 18 July 2022

Cinema Rediscovered Founder and Watershed Cinema Curator Mark Cosgrove takes us through the films that make up the When Europe Made Hollywood: From Sunrise to High Noon strand - part of Cinema Rediscovered 2022.

One of the sparks for this season was the re-issue earlier this year of Paul Verhoeven’s Robocop (1987). I first came across the Dutch director through his successful Hollywood debut only later discovering that Verhoeven was a hugely successful Dutch director before the Studios came calling. He would go onto to have a distinguished Hollywood career reshaping the thriller and sci-fi genres – and is still very much thriving between Europe and America.

Thinking about Verhoeven’s journey led me back through the history of Hollywood’s relationship with European filmmaking talent. It is of course a rich seam with those that have succeeded like Michael Curtiz, Max Steiner, Marlene Dietrich, Dimitri Tiomkin, Billy Wilder turning their European forged sensibilities to maximum successful effect in this foreign American popular medium. It is also a wide seam stretching from the early days of the studio system with the likes of F W Murnau and Josef von Sternberg through to Preminger and Hitchcock to Verhoeven, Ridley and Tony Scott and the modern era. The original season was going be titled - from Sunrise to Robocop! Too much and too unwieldy in scale for 5 days. Even this current framing - From Sunrise to High Noon - can only touch the surface. Think of each film as one of the surface touches of the skimming stone over the vast reservoir that is the European influence on Hollywood.

The framing of the season also marks three perspectives from Hollywood (America) of the European émigré. The first is success in their home country for example F.W Murnau, Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich. These were talents who were popular and successful in Europe – at the box office and creatively – who caught the attention of studio bosses with a view to replicating that success and prestige. The second was the forced migration due to the rise of Nazism in Germany and Fascism in Europe – represented here by Billy Wilder, Robert Siodmak, Fritz Lang and virtually the whole cast of Casablanca (1942.) The third was post 2nd World War when the Cold War froze the support and positivity America might have had for foreigners, the European émigré with their left leaning sensibilities were now a threat to American society in general and Hollywood in particular: here represented by High Noon (1952.) Whilst High Noon was being made, key players in and around the production were being called to testify about their Communist Party affiliations and name names of colleagues who were Communist sympathisers – invariably but not exclusively those European émigrés who had just fled fascism in Europe - publicly to the House Of Un-American Activities.

Credit: F.W. Murnau and Charles Rosher – A Song of Two Humans © 1927 Fox Film Corporation

Hollywood Calling

The driving motivation of the Hollywood studios in the early days was different from their European counterparts. The American studios was born of cheap popular entertainment whereas in Europe, this new medium could sit alongside the developments and innovation in European cultural traditions of literature, theatre, music and opera. The idea of the director as a creative force was more natural in Europe. In Germany’s UFA studio for example, directors like F.W. Murnau and Fritz Lang would explore psychological complexity and philosophical ideas through visually ambitious and formally innovative films such as Nosferatu (1922), Dr Mabuse The Gambler (1922), The Last Laugh (1924), M (1931) and Metropolis (1927), which were not only critically acclaimed but financially successful.

These two things - success at box-office and critical acclaim – then as now, always attract attention. And so it was that (Hungarian born) William Fox Head of Fox Film Corporation, partly motivated by money but also by the prestige of critical acclaim, invited Murnau to make a film for his new studio. Murnau was given creative carte blanche (some 15 years before Orson Welles. ) The resulting film Sunrise (1927) is recognised as one of the great artistic achievements of Hollywood where the dramatic developments in the visual language of filmmaking forged in the German film industry were given full reign.

Successful actors in Europe – particularly in the silent era – would similarly be scooped up by studios eager to expand their commercial markets: Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich and Ingrid Bergman are iconic luminous examples. In the 1920s and early 1930s Hollywood would keep tabs on new European talent. In different decades Garbo and Bergman came up through the thriving Swedish film industry, their screen presence and popularity in Europe attracting American producers.

Credit: Shanghai Express (1932) courtesy of Park Circus and Universal

In Dietrich’s case it was the director Josef von Sternberg who dramatically realised her on screen star quality. Von Sternberg whose impoverished family had left Vienna in 1901 to make a better life in America had acquired a reputation in silent era Hollywood as ‘the young Austrian with a streak of genius’. In the 1920s he moved quite comfortably between the American and Europe film industries his heavily expressionistic influenced style more welcome to a European sensibility. It was in one of these trips that he cast a then little-known Marlene Deitrich in his German made screen adaptation of The Blue Angel (1930). The film’s success and Deitrich’s dangerously seductive onscreen allure would lead to a unique film partnership with six films in America that redefined the visual aesthetic of Hollywood and created a screen style icon.

Credit: The Killers (1946) courtesy of Park Circus and Universal.

Exiles in Paradise

“They believed in the power of art to reason, to represent a model of civilization – a kind of rule book – which was ripped up by the rise of Nazism and which was another language in Hollywood.” The Magician, Colm Tóíbín

The rise of Nazism in Germany and Fascism in late 20s/30s Europe led increasingly to mass migration particularly those of Jewish origin to escape persecution and, as the 1930s progressed, certain death. Directors like Billy Wilder (Double Indemnity, 1944) and Robert Siodmak (The Killers, 1946) who had worked together – along with Fred Zinnemann (High Noon, 1952) – on the Berlin set People on Sunday (1929) The Nazi leaders understood the power of art and the power of the new form of cinema, quickly taking control of channels of representation and public communication. Indeed, Fritz Lang (Fury 1936) then the leading filmmaker in Germany told of how the then Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, whilst banning Lang’s The Testament of Dr Mabuse (1933) was so impressed by the power of the film, he offered Lang the job as Head of the German film studio (UFA.) Lang quickly left the country moving first to Paris then to Hollywood. This was a similar journey made in the 1930s by Wilder and Siodmak. Where Wilder quite quickly went to Hollywood from Paris, Siodmak spent a successful six years in the city making films before leaving just before war broke out in 1939. Both Wilder and Siodmak’s Hollywood films bring together their rich experience of European filmmaking and the prevailing expressionist style with a shared lived disillusioned view of humanity – much of Wilder’s family were erased in the Holocaust. Where Wilder’s film world view would be unfairly described as cynical, Siodmak’s would convey an existential sense of impending fate.

Credit: Casablanca © 1942 WBEI

Casablanca: The most European and political film ever made in Hollywood

It is easy to overlook the fact that the subject matter of this most loved, quoted, and celebrated Hollywood film was the very real and recent experience of European refugees escaping Nazi Germany. Many on the set would have had experience of trying to get out of Europe. Casablanca (1942) is populated on and off screen by very real European émigrés recent experience. Hungarian born director Michael Curtiz was trying to get his family out of Europe. Curt Bois, playing the pickpocket of the opening scenes, born into a German Jewish family was a successful stage actor who performed under Max Reinhardt. The rise of antisemitism forced Bois to leave Germany in 1934. The instigator of the film’s plot Ugarte is played by Hungarian born Peter Lorre who developed his stage career with German playwright Bertolt Brecht and came to screen success in Fritz Lang’s M (1931) left Germany in 1933. Rick’s head waiter Carl is Budapest born Hungarian stage actor S.Z.Sakall. Marcel Dalio who plays the uncredited croupier was a French actor who had worked with Jean Renoir and was married to Madeleine Lebeau who is memorably filmed rousingly singing La Marseillaise in the film. In 1940, Dalio and Lebeau used transit visas to get through Spain and onto Portugal before heading to the Americas. All Dalio’s Romanian Jewish family died in the concentration camps.

Credit: Madeleine Lebeau in Casablanca © 1942 WBEI

Major Strasser was played by celebrated German actor Conrad Veidt (another alumnus of the theatre of Max Reinhardt) who ironically would spend a lot of his exile years portraying Nazi; something which he accepted as part of trying to show the threat to an American public.

Whilst the Paris flashback scenes were being filmed, there were stories of extras breaking down in tears. Some had just lived through the recreated studio experience.

The film brought to the American – and wider – public; albeit in a fictionalised dramatic form; a very current account of what was happening because of the war in Europe. America, like Rick, had been standing on the side-lines sticking their head out for no one. This was to change in 1941 with the bombing of Pearl Harbour and Casablanca’s release a year later by presenting the journey of Rick from ideological neutrality to taking an active position in support of the resistance, did much to bolster American popular opinion in support of US involvement in the war in Europe.

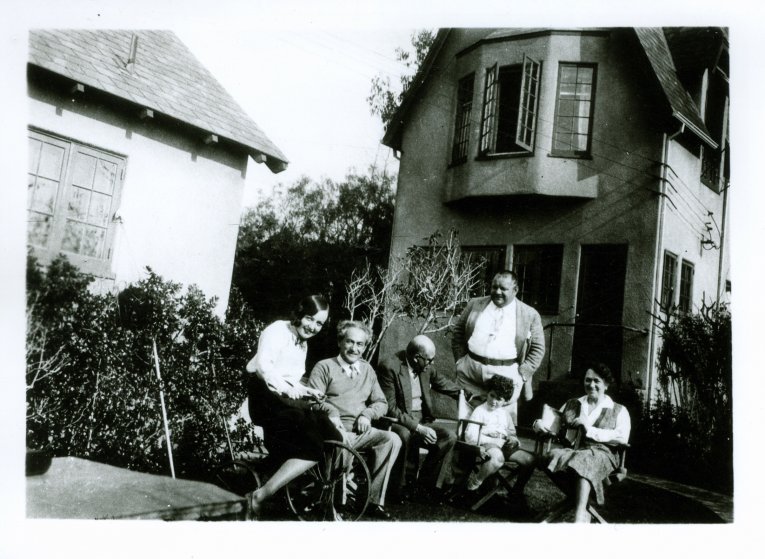

Credit: Salka Viertel and Greta Garbo, 165 Mabery Road in Santa Monica, 1930s.

Salka Viertel: Actress, Writer, Émigré Activist

There have been revelatory connections for me during the research. The importance of Austrian born theatre director /impresario Max Reinhardt who himself was forced by the rise of Nazism and antisemitism in the1930s to flee to America. The range of talent – actors, directors, producers, stage design - who came through Reinhardt’s theatrical productions and who would make their mark in Hollywood is immense. Half the cast of Casablanca (1942) alone have a Reinhardt theatrical connection including Conrad Veidt, Paul Henreid, Curt Bois. Reinhardt’s interest in film techniques would also influence visual styles and cinematography. At one point Reinhardt’s 1935 film version of his acclaimed stage production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was to be included in the season. The influence of Reinhardt on film is a season in itself!

Another lesser known but no less hugely significant European influence on Hollywood and the wider European émigré experience in America is the actress and scriptwriter Salka Viertel, herself an alumnus of Reinhardt’s theatre. Her connections in Hollywood and across European culture, her friendships and influence, her activism in helping those fleeing from Nazism, the convivial sociable environment she provided for the European émigré in Hollywood through her weekly Sunday lunches – a European salon in Santa Monica - all exerted a supportive framework for those struggling to make sense of this new world, such as Eisenstein and Brecht, and those navigating the pressures of the new phenomenon of fame like Garbo. Viertel is the golden thread that invisibly weaves the season together and it is to her generous, cultured spirit that When Europe Made Hollywood is dedicated.

Salka Viertel was born Salomea Steurmann in 1889 in Sambor, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire now Western Ukraine. Like so many with acting ambitions she came up through the Reinhardt school and with her theatre director husband Berthold Viertel became a formidable theatrical couple in Germany and Austria.

Like any thriving creative community there was a shared sense of cultural purpose and many friendships. When F.W. Murnau - one of the Viertel’s closest friends – was invited to go to Hollywood in 1926 he encouraged his friends to come join him in what was then creative equivalent of the Gold Rush! Such was the demand for German talent that the joke was that if the phone rang in one of the Berlin cultural hangouts it would be said it was Hollywood Calling. Berthold Viertel followed Murnau months later with Salka and their children following afterwards.

Figure 3: From left to right: Dita Parlo, Berthold Viertel, Arnold Schönberg, Thomas Viertel, Heinrich George, and Salka Viertel in the garden of 165 Mabery Road (early 1930s); by courtesy of Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Sammlung Franz Glück, ZPH 1443

Salka set up their Californian home on Mabery Avenue, not just for her family but for the increasing wave of European émigrés to acclimatise to this new culture. A who’s who of intellectuals and creatives from across European – Adorno, Manns (Thomas & Heinrich), Schoenberg, Garbo, Isherwood, Brecht - discussed the state of Europe in the convivial atmosphere of Viertel’s Santa Monica home. Berthold’s first assistant in Hollywood was a newly arrived nineteen-year-old Austrian Fred Zinnemann.

With the rise of Nazism in Germany, Salka Viertel was one of the co-founders of the European Film Fund, a Hollywood initiative which supported refugees not only with financial resources but support for visas to enter America. She mobilised her impressive network of contacts across Hollywood to raise awareness of, and money for, European refugees.

It would be her friendship with Greta Garbo though that stands out as Viertel’s biggest cinema influence in Hollywood. Garbo was one of the first friends Viertel made when she arrived in California, memorably drinking champagne into the night with the wary and reserved star on their first meeting. Garbo would regularly call round to go walking, swimming, and relaxing with Viertel. Such was their friendship that the studios quickly discovered they would be best to go through Salka to get to Garbo. Viertel was herself an established actress – which probably helped forge a bond with Garbo – and was developing as a scriptwriter. She and Garbo would discuss future roles and often Garbo would insist that scripts which she was sent had to have Viertel’s approval. It was Viertel who conceived of Queen Christina (1933) for Garbo and who researched and wrote the first draft. Queen Christina would be one of the last Hollywood films shown in The Third Reich.

High Noon

Like many European exiles and refugees Viertel would suffer under the 1950s Cold War suspicion of foreigners. After the war and with mounting suspicions of the USSR and Stalin, America defaulted to its fear of outsiders with unabashed vigour mounting a political campaign to rid American society of ‘the red under the bed’. Hollywood was quite quickly a very public target – and vote winner for populist politicians seeking publicity – when the House of Unamerican Activities Committee (HUAC) turned their frenzied attention to the renewed spectre of Communism. Willing and unwilling alike were called publicly in front of the committee not only to attest to their political loyalties but to name names of anyone they knew with communist connections. Many, that had fled Fascism and Nazism in Europe a decade before, were either communist party members, campaigned or had affinities with the progressive left. The committee brokered no nuance conflating the personal and the political and forcing ‘witnesses’ to not only indict themselves but to name others. Many Hollywood careers were left ruined. Playwright Bertold Brecht testified in a testy hearing to the committee and left America the next day - he had experienced this kind of behaviour before!

High Noon (1952) Gary Cooper Courtesy of: Park Circus and Paramount

This pressure on personal decision is given great cinematic representation in Fred Zinnemann’s 1952 High Noon. Written and produced by Carl Foreman the dilemma of Marshall Will Kane (Gary Cooper) on screen captured the very real pressure of being called to testify that was swirling round Hollywood. Also, the idea of what true American values were was very much at stake and High Noon’s reframing of the West - as a place for debate, a self-serving community and equivocating masculinity – would challenge those who believed in the Hollywood origin myth of the Wild West where “a man’s got to do what a man’s got to do”. High Noon would famously rile that Western icon and staunch Republican John Wayne.

Foreman’s parents were Russian Jews who emigrated to Europe in the early 1900s to escape poverty. Carl Foreman, born in Chicago and first generation American, would, in an ironic twist of fate, represent a new wave of forced migration from America to Europe for Hollywood directors like, Joseph Losey and Cy Endfield, who would forge successful careers in exile. Foreman himself would go on to be a successful writer/producer in the UK working on films like Bridge Over the River Kwai (1957, uncredited), The Guns of Navarone (1961, Producer) - directed by Bristol Born J. Lee Thompson - and Mackenna’s Gold (1969, Producer).

Always supportive of new talent Foremen gave training opportunities to aspiring filmmakers. On MacKenna’s Gold he asked the trainees to make a documentary about the making of the film. Of the four he would clash with one, who was only interested in filming the desert when they were on location that trainee was George Lucas. Lucas would later say of Foreman “he was a very important significant person in my life as I was growing up because he was one of the first people who, from the professional community, took an interest in me” That interest in supporting new talent would inform this Hollywood exile in Europe’s impact on UK filmmaking via his governorship of the BFI and early iteration of the National Film and Television School. Therein lies a future season.

When Europe Made Hollywood: From Sunrise to High Noon is presented by Watershed Cinema Curator, Mark Cosgrove in collaboration with archive activists Invisible Women and Park Circus as part of Cinema Rediscovered on Tour, a Watershed project with support from BFI awarding funds from The National Lottery and MUBI.

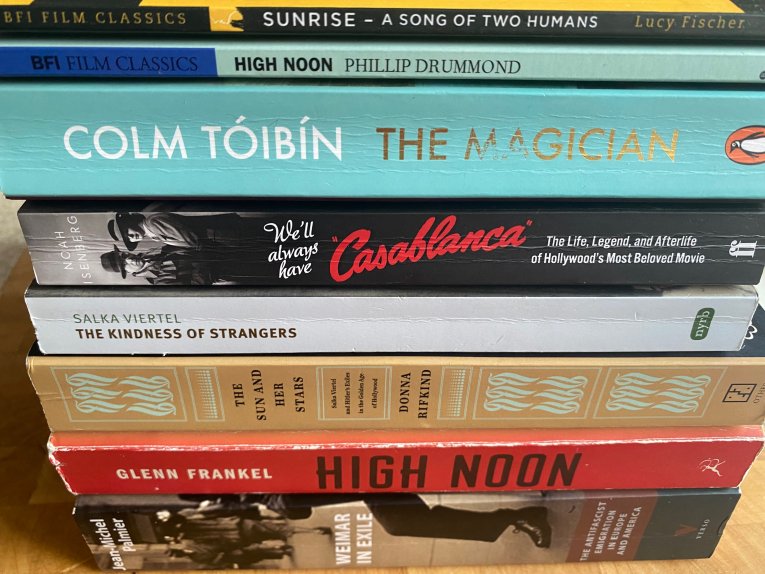

For further reading, here’s Mark’s book recommendations:

- Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans by Lucy Fischer (BFI Film Classics)

- High Noon by Phillip Drummond (BFI Film Classics)

- The Magician by Colm Tóibín (Penguin)

- We'll Always Have Casablanca: The Life, Legend, and Afterlife of Hollywoods Most Beloved Movie by Noah Isenberg (Faber & Faber)

- The Kindness of Strangers by Salka Viertel (New York Review Books Classics)

- The Salon of Exiled Artists in California by Núria Añó (independently published)

- The Sun and Her Stars: Salka Viertel and Hitler's Exiles in the Golden Age of Hollywood by Donna Rifkind (Other Press)

- High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic, Deckle Edge by Glenn Frankel (Bloomsbury)

- Weimar in Exile: The Antifascist Emigration in Europe and America by Jean-Michel Palmier (Verso)