Andy Willis Professor of Film Studies at the University of Salford and Senior Visiting Curator at HOME, Manchester

on Tue 25 July 2023Look Who’s Back: the Hollywood Renaissance and the Blacklist

Posted on Tue 25 July 2023

Andy Willis (Professor of Film Studies at the University of Salford and Senior Visiting Curator at HOME in Manchester), curator of the Look Who's Back: The Hollywood Renaissance and the Blacklist strand at this year's Cinema Rediscovered festival, dives into the thinking behind the strand and the political context of this era of Hollywood filmmaking.

Much has been written about the renaissance in Hollywood cinema in the late 1960s and early 1970s, an era which saw films tackling tougher subjects and challenging older, conservative views. The fact that this has often been portrayed as a moment when new voices, particularly those of a younger generation of creatives, got their chance in the mainstream has meant that the contribution of a previous group of Hollywood practitioners – those blacklisted in the 1940s and 1950s – has been overlooked. The ‘Look Who’s Back: The Hollywood Renaissance and the Blacklist’ strand at this year’s Cinema Rediscovered offers audiences the opportunity to revisit the involvement of some of those blacklistees to the new Hollywood cinema of the late 60s and 70s through a series of screenings of well-known and not so familiar titles.

The Hollywood blacklist was an attempt to counter a perceived communist influence in Tinsel Town’s output. It began in the years after the end of World War II when some of the USA’s former allies, particularly the Soviet Union, now became enemies. As early as 1946 the film industry trade paper The Hollywood Reporter began to publish articles that suggested communist sympathisers were working in Hollywood and, crucially, that something should be done about it.

Following these accusations, in 1947 The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began to investigate the supposed presence of communists in Hollywood. Whilst some figures on the political right, such as Walt Disney and Ronald Reagan, were happy to testify and denounce those they saw as communist supporters, nineteen of those called to testify before HUAC were labelled as hostile. Eleven of those appeared before the committee and refused to co-operate fully, with ten charged with contempt of congress, whilst the other – dramatist Bertolt Brecht – spoke to the committee and then promptly left America for Europe. Those who remained subsequently became known as ‘The Hollywood 10’.

In November 1947 a number of major studio heads, including Louis B. Mayer, Samuel Goldwyn and Albert Warner, released what became known as the ‘Waldorf Statement’. This denounced the Hollywood 10 and stated that they would not knowingly hire a communist at their studios. This led to the instigation of a blacklist which had a real and significant impact on the careers of a range of Hollywood practitioners.

By 1950 The Hollywood 10 had been sentenced to a year in prison for contempt and the pamphlet, Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television, had named another 151 actors, writers, musicians, broadcast journalists and technicians suspected of being communist sympathisers. This led to many being called before HUAC, and the blacklisting of those who refused to collaborate. Those who did co-operate offered the names of others suspected of communist sympathies. Often mere hearsay, this led to many being blacklisted due to association rather than hard evidence.

As the 1950s progressed many of those blacklisted, including writers and composers, were forced to work under pseudonyms or fronts, often for much less renumeration than they were able to demand in their Hollywood heydays. However, in the case of directors and actors, for whom this route was more difficult given their presence on set, the blacklist led to either exile or inactivity, with many not being able to work in America again until the 1960s.

This aspect of the blacklist led to a number of quite ridiculous events. For example in 1957, The Brave One, scripted by Dalton Trumbo (one of the Hollywood 10), won the Best Screenplay Oscar for a fictitious Robert Rich. In the same year, two other blacklisted writers, Carl Forman and Michael Wilson, wrote the script for The Bridge on the River Kwai only for the author of the original novel it was based on, Pierre Boulle (who was rumoured not to speak a word of English), to be given the on-screen writing credit. To make matters more farcical, in 1958 the film was awarded the Oscar for best adapted screenplay. It would not be until 1985 that Forman and Wilson would be awarded posthumous Oscars for their The Bridge on the River Kwai script.

1960 is widely seen as the year the blacklist began to break down, with Dalton Trumbo being given on-screen credits for his work on the screenplays of both Spartacus, which was released in the USA in October 1960, and Exodus, which was released in December. However, many of those who had endured the blacklist would not return to making films in American until much later in that decade. In fact, the 1960s would see the return to the mainstream of a number of film professionals who had been blacklisted in the late 1940s and 1950s. This is perhaps unsurprising when one considers that during the late 1960s and early 1970s America was experiencing significant social and political upheaval. Inspired by the fight for civil rights and the growing anti-war movement, as well as other campaigns for social justice, these filmmakers discovered their leftist and progressive politics had the potential to once again connect with audiences. As a result, they found fresh collaborators in the youthful and radical voices within the new American cinema of the period.

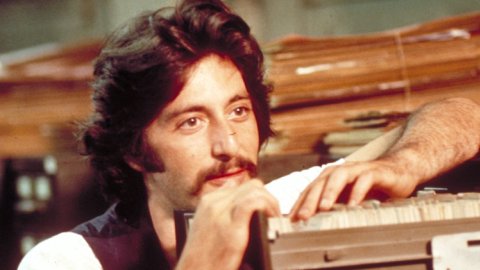

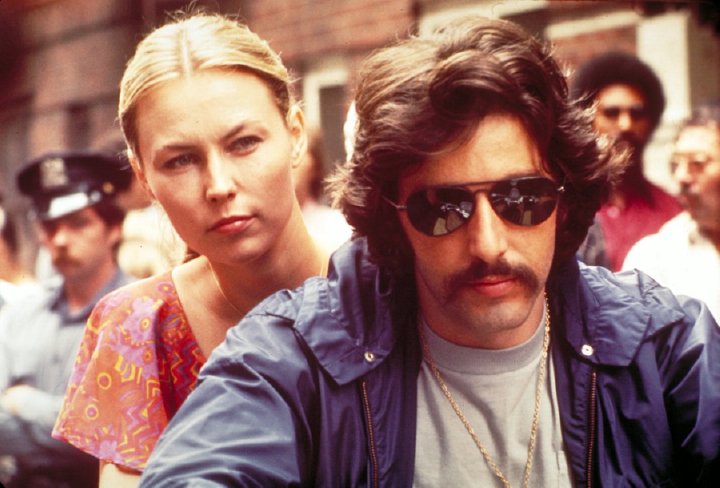

This series of screenings invites you to re-think the contribution of the Hollywood blacklistees to American cinema of the late 1960s and 1970s. Far from being the spent creative force as they are often represented, these films show that formerly blacklisted directors (Jules Dassin (Uptight), John Berry (Claudine), Abraham Polonsky (Tell Them Willie Boy is Here)), actors (Lee Grant (Shampoo)) and screenwriters (Ring Lardner Jnr (M*A*S*H), Waldo Salt (Midnight Cowboy and Serpico)) made a vital contribution to the reinvigoration of cinema in one of Hollywood’s most creative eras.

After its launch at Cinema Rediscovered from Thu 27 – Sun 20 July, Look Who’s Back: the Hollywood Renaissance and the Blacklist tours to venues across the UK with the support of BFI awarding funds from National Lottery.