Tom Vincent

on Tue 18 June 2019Analogue Rules! Beginner's guide to reel film

Posted on Tue 18 June 2019

Today, if you go the cinema to watch a new movie, it is almost a certainty you will be watching a digitally projected moving image but at this year’s Cinema Rediscovered, you will have the chance to see some films on film. And, if you visit the Analogue Room, you will have the opportunity to handle 35mm film and try your hand at splicing and projecting, too, Aardman Archivist Tom Vincent writes.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the first commercial digital projection in a cinema and, two decades later, the Digital Cinema Package (DCP) has now replaced 35mm film as the dominant distribution and exhibition format. Whilst watching movies projected on film is becoming increasingly rare, some cinemas still maintain film projection equipment, including Watershed, which has film projection capability in all three of its screens. When projecting a film print, the projectionist needs to consider a variety of options such as aspect ratio, sound format, and speed.

Pictured above: still from Morgan Fisher's 1984 film, Standard Gauge

What is 35mm?

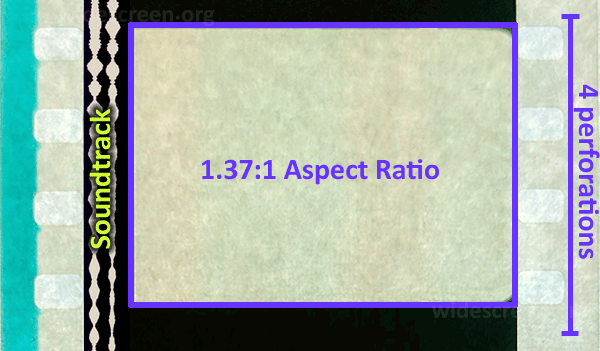

35mm is the most common film format used in cinemas. The film is 35mm wide with four perforations on both sides, which are used to transport it within the camera and projector mechanisms. Motion picture film is made of two main components: the base and emulsion, the layer that contains the photographic materials.

Why 35mm?

The early years of motion pictures were like the Wild West. In the 1890s and early 1900s, lots of companies and inventors were competing against each other, which resulted in many films in different widths. However, in order for the industry to flourish, a standardised film gauge was a necessity. It meant that film producers, distributors and exhibitors could invest in equipment in the knowledge that it would be compatible with others. Thanks largely to the early dominance of the Edison and Lumière companies, 35mm was standardised by the American Motion Picture Patents Company in 1909.

Pictured above: still from Bill Morrison's 2016 documentary, Dawson City: Frozen Time

Celluloid

For the first six decades, 35mm film stock was mostly made out of a plasticised nitrocellulose. This stock can be referred to as cellulose nitrate or celluloid. Unfortunately, as celluloid was a highly flammable material, it was phased out in the early 1950s due to safety concerns. It was replaced by ‘Safety Film’ (cellulose acetate), which is still manufactured today. New 35mm prints are now made on a polyester-based stock (which is nearly impossible to tear!)

The word ‘celluloid’ is frequently used as a general term for film stock, but this is inaccurate, as it has not been manufactured for use in motion pictures in seven decades!

Speed

The speed films are projected at are usually measured in frames per second (fps). Sometimes, the speed is measured by the length of film going through the projector or camera. For example, at 24fps, 35mm film runs at 90ft per minute.

Between the 1890s and 1920s, film speed was not standardised. So, when projecting a silent film from this period, settling on a speed can be difficult. Luckily, excellent research work by film historians and archivists has proven to be an invaluable resource for silent film presentation. When the ‘talkies’ arrived in the late 1920s, film speed was standardised at 24fps, which is still in use today.

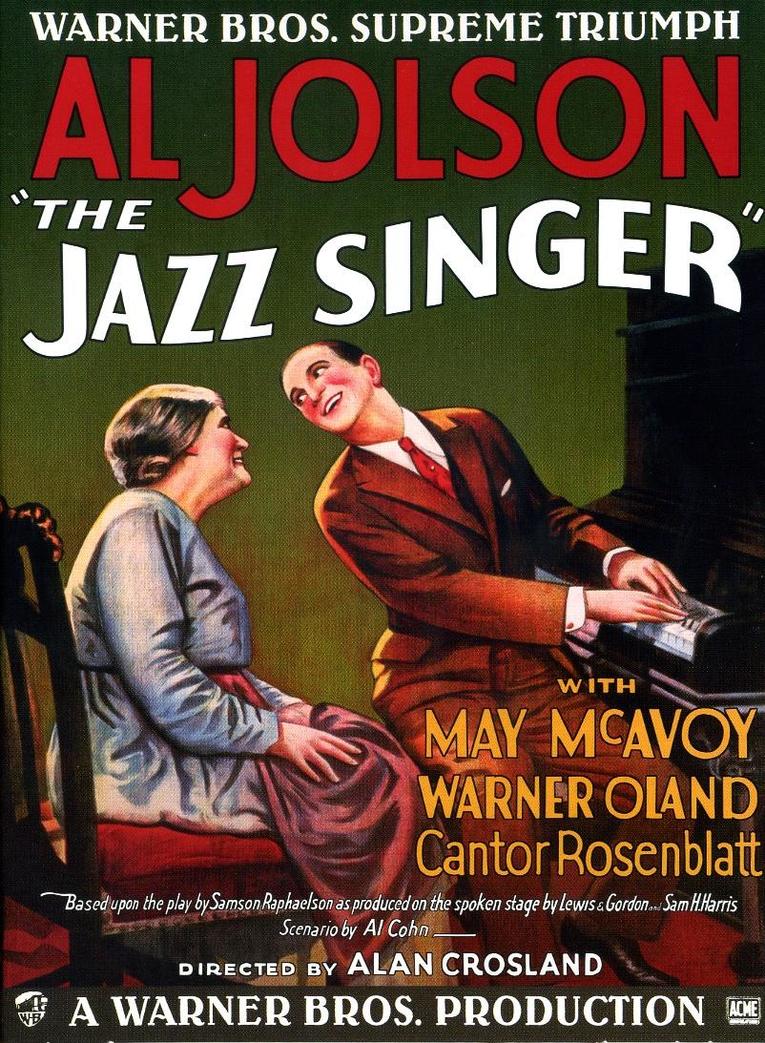

Sound

Experiments with synchronised sound began almost as early as the first film projections. Even though it was not the first sound film, 1927 hit The Jazz Singer famously heralded the new era of “Talking Pictures”. Released using the Vitaphone system, it had its soundtrack recorded on a phonograph record, which was played back synchronised to the projector. Sound-on-disc sound formats did not endure, as sound-on-film became the norm.

The most enduring sound-on-film format is the optical soundtrack, where analogue audio is encoded on an area to the side of the picture frame. These tracks will appear as either a variable area track or variable density. A sound head on a projector will read these tracks. If you look at a piece of film and see a couple of wavy lines: that will be the optical soundtrack! In the 1970s, Dolby’s noise reduction and stereo encoding technology became an additional option for the optical soundtrack.

In the 1990s, digital sound was added to 35mm. The most common method was to encode the data on the film itself. On Dolby Digital encoded film prints, the data was added in the area between the perforations.

Colour

Like sound, experiments in colour began at the dawn of motion pictures. It was very common for silent films to be tinted or toned (or both), where the film was bathed in a colour dye. For example, blue tints were frequently used to depict scenes set at night. Individual parts of the image were also sometimes coloured, using a stencilling method or even by hand.

There were hundreds of competing natural colour systems, but the most famous was undoubtedly Technicolor. There were a few Technicolor processes from 1916 onwards, but the 1930s introduced the most iconic: Three-Strip Technicolor. Three black and white films went through the camera, each one recording the red, blue and green record. Technicolor prints (I.B. Tech) were made using an imbibition dye transfer method: matrices made from the camera negatives were printed onto a blank receiving film using yellow, cyan and magenta dyes. The 1950s saw the end of the Three-Strip Technicolor camera with the rise of colour negative film stocks such as Eastmancolor, although Technicolor dye transfer printing continued until the 1970s, with a brief revival in the late 1990s.

Aspect Ratio

Aspect ratio is the proportional relationship between the width and height of an image. When 35mm was standardised in 1909, the aspect ratio was also standardised to 1.33:1, where the width was 1.33 times wider than the height. With the advent of the sound-on-film formats, the image became narrower to accommodate the soundtrack. In 1932, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences standardised the aspect ratio to accommodate the soundtrack by slightly reducing the height of the frame. This became the “Academy Ratio” of 1.37:1.

The 1950s saw the film industry face new challenges, including the increasing competition of television. Audience attendances were dwindling and the industry needed an added attraction for moviegoers. 3-D! Stereophonic Sound! However, the most enduring response was a simple one: make the movies bigger!

The success of the three-projector, ultra-wide Cinerama process in 1952 kickstarted Hollywood’s introduction of various widescreen systems, including CinemaScope, SuperScope and Techniscope. The film gauge also got bigger, most notably the 70mm processes such as Todd-AO and Super Panavision 70. VistaVision was a process where 35mm went horizontally through the camera: the 8-perforation camera negative resulted in an image approximately 2.5 times larger than standard 35mm (Simon & Laura, shot in VistaVision, is being screened at the festival).

Eventually, the 35mm standard eventually settled on two aspect ratios: standard widescreen (principally 1.85:1, but can be anything from 1.65:1 to 2.00:1), and anamorphic widescreen, which squeezes a wide image using a special lens (2.35:1 or 2.40:1). The current digital cinema standard specifies two aspect ratios: 1.85:1 and 2.39:1.

Small Gauges

16mm film was introduced by the Eastman Kodak company in 1923. It was initially marketed as a cheaper film alternative for the amateur enthusiast, but it soon became popular in the production of industrial, educational and documentary films. Studio films were also released on 16mm for additional markets like cinema clubs and home viewing. 16mm became a prolific format used in low-budget features, artists’ films and television production. Watershed has a fully working 16mm projector in Screen 1.

Other small gauges include 28mm (introduced in 1912), 9.5mm (1922), Standard 8mm (1932) and Super 8mm (1965).

Pictured above: Mark Jenkin's 2019 film, Bait, shot on 16mm, will be distributed on DCP but with 35mm film print screenings for UK preview + Q&A tour in August.

Film Today

Despite the dominance of digital in today’s movie industry, film is still used. Some of the biggest blockbusters are still shot on film, such as the latest Star Wars and James Bond movies, and film prints are still being made in limited runs for special engagements, including Mark Jenkin’s forthcoming UK Q&A tour with a 35mm film print of his new feature film, Bait.

Written by Tom Vincent for Cinema Rediscovered.

*Top image from Julia Marchese's 2014 documentary, Out of Print.