Zoe Rasbash Environmental Emergencies Action Researcher

on Fri 5 Sept 2025Five Years of Climate Action at Watershed - Part 2

Posted on Fri 5 Sept 2025

Zoe Rasbash has been Watershed's Environmental Emergencies Action Researcher for the past five years. As she leaves us for new challenges she takes some time to reflect on all that she, and we have learned. This is the second of a two-part article.

PART TWO: The contradictions of climate work

In Part One, Zoe Rasbash (Environmental Emergencies Action Researcher at Watershed) shared how the focus on decarbonisation feels increasingly futile in the face of the systemic causes of climate injustice. Here she discusses how these systems show up in the day-to-day operations of Watershed, and the work we are doing to nurture the seeds of alternatives.

“If you have come here to help me you are wasting your time, but if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” - Lila Watson

Across nearly every element of climate action at Watershed we face a difficult balancing act: remain affordable for our communities while purchasing as ethically as possible, attempt to think a generation into the future while clawing ourselves of COVID deficit, be both ambitious and realistic.

Let me share a few examples of how this shows up day to day.

First up is our net-zero goal. We have realised that our target is nearly impossible without employing carbon offsets. For an organisation like us to offset our emissions with rigorous carbon pricing would cost up to £70,000 a year - money that we simply don't have. Especially when we are committed to holistic sustainability: we must retain a living wage for all our employees and offer affordable cultural experiences for Bristolians. Should we prioritise offsetting when our carbon footprint (compared with the largest cultural institutions in the UK) is tiny?

Carbon offsetting itself raises serious ethical questions. Many climate justice activists describe offsetting as a form of green colonialism when it relies on land in the Global South for carbon sequestration, displacing local communities and shifting the burden of climate action onto those least responsible for emissions. Do we remain dedicated to our targets despite limited resources, do we employ controversial offset schemes, or do we follow the values of our organisation and bring these complex ethical questions into the light- potentially at the cost of our stated climate ambitions?

Our cinema advertising is a further dilemma. Earlier this year, I had a difficult conversation with an audience member concerned with how advertising cars before films doesn't align with our climate goals. They were right to question this. But our communications team has already eliminated many advertisements that don't align with our other values (gambling, fast food, military recruitment) and we must keep some advertising to help fund the diverse, challenging, independent films that our community loves.

In Pervasive Media Studio we are dedicated to critically interrogating technology. But the technology we use, that our communities create with and the ‘clean technology’ that is sold to decarbonise operations all raise complex ethical questions. Most technology infrastructure and supply chains are reliant on material and labour exploited from the Global South. What does this mean for us as a community? When the transition to a decarbonised world necessitates redoubling colonial extraction, but not acting leads to horrendous climate impacts on those least responsible for the crisis, what do we do then?

Our building exemplifies these contradictions. We need to retrofit our building and we are striving to do this in the most socially and ecologically responsible way possible. But the reality is that construction materials and new technologies have their own substantial environmental footprints and regenerative approaches are much more expensive.

We want to revitalise the neglected areas around our building to provide cool, vibrant, green areas in the city centre. We have received heritage funding to begin this work, and are striving to understand the natural and social heritage of the harbourside. Our building, and the wider harbourside area, has a complex history as both a centre of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and of post-industrial decline. To develop this area to be climate resilient, accessible and inclusive we have to consider our historical responsibility as stewards of this building. What questions does this raise for how different communities experience and feel welcome in our spaces? There are no simple answers.

The polycrises affect everyone in our community differently: some have family experiencing chronic drought, wildfires, and floods in vulnerable areas across the world; others are experiencing the devastating violence of IDF military technology funded by UK corporations. As migration increases due to these events, racialised folks in our community are faced with horrendous violence stoked by right-wing media and politicians. These power dynamics show up on the interpersonal level, with those most impacted by systems of oppression most often bearing the exhausting emotional labour of calling them out, and those in positions of power often unable to truly hear and understand.

We know we cannot extract ourselves as an organisation from these larger systems of oppression and have been collectively figuring out how we can challenge them. What is our role as an organisation in these violent, terrifying times? How do we keep our staff members and audiences safe? What is the relationship between our charity status and political messaging? This is the mess; balancing urgency with nuance and care, trying to work in a participatory way, finding our way with no clear roadmap, keeping going while resisting the system where we can.

Seeds of change

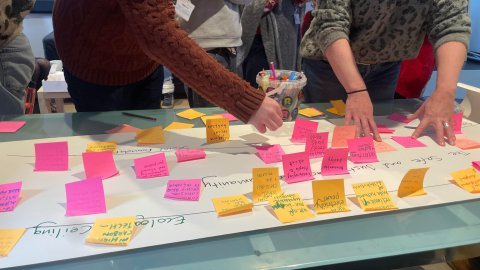

To build a different way of being is to nurture and visibilise seeds of change. This work is slow, partial and often messy. But I have witnessed it happening in many different areas of Watershed, through experiments and commitments that challenge dominant ways of working to try and root something more equitable.

This can look like policies we write and rewrite, or changes to the physical building we sit in – but most often it lives in the emotional, relational labour done every day by people in our community. In the staff members who consistently go against the grain, advocating for their communities in spaces where they are not always heard and have to repeat themselves time and again. In those who listen deeply to feedback and criticism from community members and spearhead our organisational reflection and evolution.

The heart of this work lives in the creative resilience of our network of creatives, making bold challenging work in an economic context that is cruel to freelance artists. And in our guest curators bringing underrepresented perspectives to our screens, inviting Bristolians into conversations that matter. I feel very lucky to constantly learn from them.

These seeds are visible in how we consider our stewardship of space – like our accessible, gender-neutral toilet refurb, created with love and intention as a public resource stocked with free period products. The essence of this has deepened the ambition of our building transformation plans, from simply retrofitting to asking how we transform our building to be a piece of climate adapted, accessible, wild and generous infrastructure of the future.

This work is also shaped by the partnerships we choose. Collaborations like the one with WECIL, whose expertise helps us challenge ableism more meaningfully. Or being part of the Just Transition Declaration, which helps guide us toward an equitable green future.

The gift economy of Pervasive Media Studio works to create a reciprocal, trusting environment where ideas can grow within a convivial space. Our Café Bar actively uplifts local producers, taking small but deliberate steps to reduce harm and support our local economy.

None of these things are complete or perfect, but partial experiments in what it means to move systems that harm. Alongside that experimentation comes responsibility: for the organisation and individuals that hold power to stay committed when it is uncomfortable or complex, to recognise that the labour of change is not equally shared. Too often, community members from marginalised backgrounds carry this weight, calling out and pushing for change without the recognition or resource they deserve.

So how do we more fairly distribute this labour? What does it mean to be accountable in this work which is hard to measure, systemic, interpersonal, and crucially, non-linear? What might shared, collective responsibility for change look like in practice? These are the questions running through my mind and if you are interested in joining us in these conversations, we’d love to talk. You can email us at climateaction@watershed.co.uk