James Harrison

on Tue 24 July 2018Slocombe at Ealing: the early years

Posted on Tue 24 July 2018

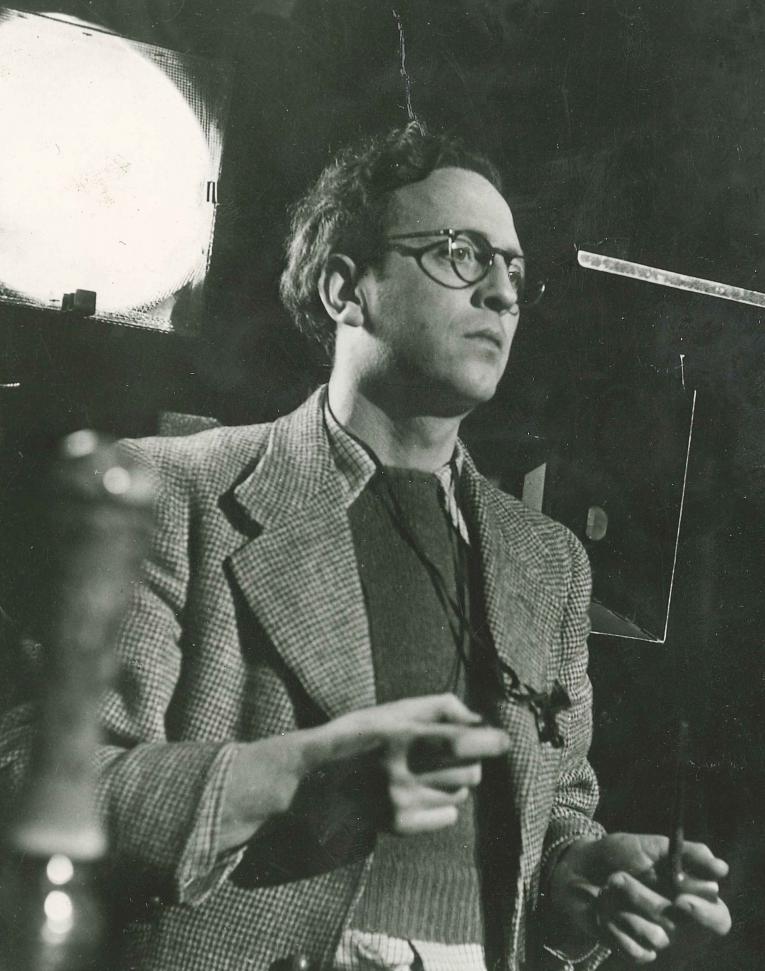

For this third year of Cinema Rediscovered we celebrate two rarities in Douglas Slocombe’s filmography, from his early years at Ealing Studios. The films are worlds apart when it comes to style, and yet, were filmed within the course of a few months, co-director and co-curator of South West Silents, James Harrison, writes.

At the end of WWII, Douglas Slocombe found himself standing at the entrance of a film studio, on the west side of London. Familiar footing for Slocombe, he had returned to the now famous Ealing Studios. Having already worked with Herbert Kline on his documentary Lights Out in Europe (1940), Slocombe’s name cropped up in conversation. Kline just so happened to be talking with his friend and filmmaker Alberto Cavalcanti, who was in the market for an adventurous cinematographer, capable of producing wartime film footage for the studio’s stock archives.

Impressed with what he saw in Kline’s documentary, Cavalcanti put Slocombe on Ealing’s payroll. Over the course of the following war years, Slocombe found himself shooting on Atlantic convoys, numerous battleships and in and out of airborne fighter planes. The footage would later be used in Ministry of Information films as well as in Ealing feature films such as Ships with Wings (1941), The Big Blockade (1942), Find, Fix and Strike (1942), San Demetrio London (1943) and For Those in Peril (1944), to name but a few.

But, on the odd occasion when he wasn’t out at sea or in the air, Slocombe was given brief periods of respite to film on the ground in Britain. One of the first for which he was credited appeared in the directorial debut of another famous name for Ealing Studios, Charles Crichton with Painted Boats (1945), a much forgotten but beautiful film set on the Northamptonshire section of the Grand Union Canal. Another key title Slocombe was credited with during this period is the now celebrated WWII invasion thriller Went the Day Well (1942). Here, he is credited as a ‘reporter cameraman’ for a now infamous sequence involving the local Home Guard and undercover Nazi invaders.

During peace time, he found his name attached to key post-war Ealing films such as Dead of Night (1945), The Captive Heart (1946) and Hue and Cry (1947). It isn’t that surprising, then, that by 1948, aged thirty-five, Slocombe’s name was well-established as one of Ealing’s key cinematographers.

The Loves of Joanna Godden (1947)

Filmed on location, during the late summer of 1946 with partial sequences shot throughout the winter of 1946 and 1947, The Loves of Joanna Godden is not just a film about characters, but also of a landscape. The rustic, sweeping countryside of Romney Marsh, Kent, is a diverse geographical place from wetlands to marshland, across open farming plains and shingle beaches. Kent proved the perfect location for adapting Sheila Kaye-Smith’s 1926 novel.

Little is known about life on set or the wider history of the film but, what it is known, is that Slocombe was the perfect candidate for the production owing to his adaptability in working on unpredictable and even challenging locations. Romney Marsh’s weather conditions would change dramatically within minutes due to the winds from the south east coast, meaning that Slocombe would have had to contend with overcast skies and, as the south-eastly wind picked up, short powerful showers or blazing sunshine - possibly both. Armed with a simple foot candle light meter, he would scan the skies to see just how long production had between takes and adjust the cameras accordingly.

Saraband for Dead Lovers (1948)

Ealing’s first Technicolor film was filmed almost entirely within the studio - with the exception of a few exteriors filmed in Prague. With this advance in technology concerning colour, a number of new issues cropped up, specifically Technicolor’s now infamous ‘quality control’ group, who would personally oversee every aspect in filming on any production that was using Technicolor cameras. Technicolor insisted that all of the films using their colour process must adhere to their standards. Slocombe, however, had other plans, constantly disappearing whenever the group arrived on set. Slocombe wasn’t after the standard Technicolor look when it came to capturing Saraband’s unique colour palette,

‘’The primary consideration when viewing colour on the screen should not be whether the hues are true to life. . . I do not know whether Technicolor Ltd have ever claimed that their process does reproduce all the colours of the spectrum faithfully. In any case, any such claim would presuppose all sorts of basic theories. It would presuppose, for instance, that there is such a thing as true or pure colour. . . In consultation with the director and art director it was decided to play for low key effects for all the day interiors as well as the night interiors. The Hanover Palace sets were therefore lit in such a manner as to cast large areas in shadow, usually allowing the ceilings to disappear into inky blackness. . . careful lighting of selected colours in the set and costumes of the artistes helped to add another dimension to the composition of each scene.”

When compared with the use of colour in other Technicolor films of the era, particularly Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (1948) (which had only been released a couple of weeks before Saraband) the differences are considerable. The Red Shoes screams with colour at every turn, while Saraband’s colours are reserved. Saraband for Dead Lovers is, as such, a very unique film from the period, and another key example of the important role Douglas Slocombe played as cinematographer.

Following the completion of Ealing’s first ever Techincolor film, Slocombe was given a new challenge: to film an actor playing nine characters in the one film - but the story of Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949) will have to wait for another day. . .

Written by James Harrison (South West Silents), with thanks to Georgina Slocombe, film critic and MOMA Curator David Kehr and writer, historian and presenter Matthew Sweet.

The Loves of Joanna Godden (Sun 29 July, 10:20 ) and Saraband for Dead Lovers (Sun 29 July, 15:10) screen as part of Cinema Rediscovered.