Tara Judah

on Wed 19 June 2019Politically potent unpleasant appetites

Posted on Wed 19 June 2019

The films belonging to Gluttony, Decadence & Resistance were all selected for their interest in asking us, as viewers, to think, feel and step outside of the safety of seeing films as entertainment, letting them instead activate us through an aesthetics and affect of excess that was designed to disgust and disrupt.

Gluttony

In addition to the general associations of greed and excess that gluttony evokes, it’s religious – and specifically Christian – connotations of desire suggest that the so-called sin is already present, before any act is committed. Wanting or yearning for excess, for that which is more than what we need, is already deadly. Gluttony, then, is a perfect match for capitalism and social systems where class, gender and other hierarchies mean too much for some at the expense of others. It is an inherently disgusting desire and its manifestation, each of these films reveals, is physical grotesquery.

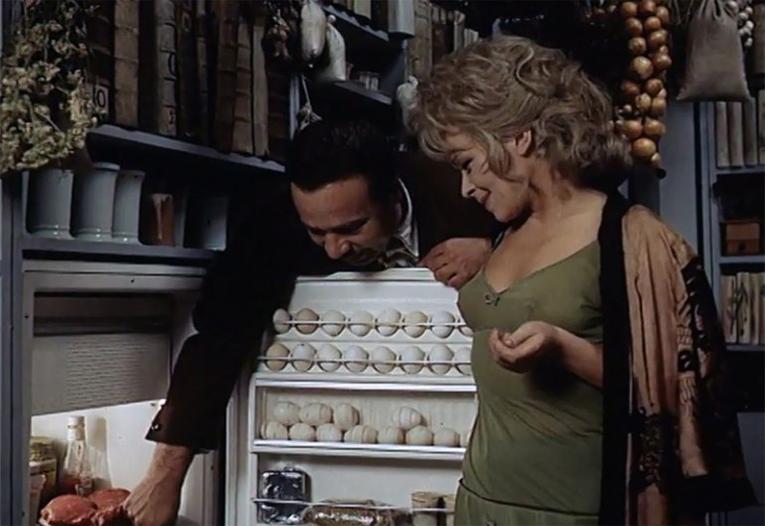

When La Grande Bouffe (Sat 27 July, 11:00) premiered at the Cannes film festival in 1973, it was met with shock and outrage – or so at least the glorious mythology of reviews and press stories would have us believe – they are, honestly, almost too fantastic to be true!

They begin with Jury President that year, Ingrid Bergman, vomiting after the screening, whilst others spat at director Marco Ferreri as he exited, and extend all the way to Catherine Deneuve apparently giving her then partner and one of the stars of the film, Marcello Mastroianni, the silent treatment for a full week afterwards. Better still, the Italians at the festival apparently disowned Ferreri, insisting the film was not Italian at all, but French (it is in the French language). The publicity also supposedly boasted that it became the largest-grossing release in Paris history, despite, as Roger Ebert writes, “inspiring fistfights and insults on the Champs Elysees.” Still, it was awarded the International Film Critics’ Prize. Whatever the real and varied responses to the film were, it’s certainly endured as a visceral feast of most disgusting proportions – the four wealthy, bourgie men at the heart of the story have, after all, decided to eat themselves to death.

Decadence

When critics saw Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (Sun 28 July, 11:00) they were again shocked by visceral affect. Roger Ebert, keen to make sense of Greenaway’s departure from his earlier, softer visuals in The Draughtsman’s Contract and A Zed and Two Noughts, suggested Greenaway was angry, pointing to readings of the film against UK politics of the time,

“The motivation was anger - the same anger that has inspired large and sometimes violent British crowds to demonstrating against Margaret Thatcher's poll tax that whips the poor and coddles the rich. Some British critics are reading the movie this way: Cook = Civil servants, dutiful citizens. Thief = Thatcher's arrogance and support of the greedy. Wife = Britannia Lover = Ineffectual opposition by leftists and intellectuals. This provides a neat formula, and allows us to read the movie as a political parable.”

But what really troubled Ebert was how such a film, and indeed such violence of politics both on and off screen, caused a classification nightmare in the US. The MPAA refused the film an R rating, which is, in essence, leaving its distributor with the option of releasing with an X - a strictly pornographic rating that means cinemas won’t touch it – or running an unrated release, equally as tricky in assuring an audience. This also led to a far shorter version of the film being released for home entertainment on VHS in the 1990s; there exists an R-rated cut at 95 minutes where the original version runs a far lengthier 124 minutes.

Controversy aside, the film is a masterful piece of visual and aural making. With costumes designed by Jean Paul Gaultier and an unforgettable, tension mounting score from Michael Nyman, Greenaway’s film is drenched in the kind of cinematic excess – both beautifully decadent and hideously gluttonous at once – that alone is enough to give you heartburn.

I think, though, that Caryn James, writing for The New York Times, puts it best in contemplating the demise of that thing we call society,

“If the most crass and sadistic people gained power, what would happen to the social order, to art and, above all, to love? This is the question Peter Greenaway explores in his elegant, stylized and brutal new film.”

Equally as bold, though at least twice as crass, is Brian Yuzna’s Society* (Fri 26 July, 20:30 at 20th Century Flicks' Videodrome), which takes visceral to new heights and has all the subtlety of a jackhammer in so doing. But not all of the films that examine gluttony, decadence and resistance are so sensorially assaulting – though they resonate just as well with the social, political and environmental concerns of today; far from decadent, Soylent Green* (Sun 28 July, 14:00 at Curzon Cinema & Arts in Clevedon) is concerned with poverty and a lack of natural resources to accommodate the population.

Resistance

Yet nowhere is the spirit of resistance greater than in the experimental formal vibrancy of the Czech New Wave. Combining humour and dissent to tug on their audiences’ social and political strings, Vera Chytilová and her screenwriting partner and costume designer, Ester Krumbachová, both created playful yet disruptive films in the face of crushing reform following the Prague Spring of 1968.

The two had already worked together in 1966 on Daisies – now considered one of the seminal films of its era, revealing the superfluous nature of aristocracy and patriarchy with aplomb. Teaming up again on Fruit of Paradise (Fri 26 July, 18:00), the pair created another experiment in allegory. Taking the story of Adam and Eve as a departure point, the film reveals so-called ‘original sin’ for the betrayal of freedom that it is, reflecting the invasion of Prague by Soviet forces in 1968.

It was also at this time that Krumbachová tried her own hand at directing with The Murder of Mr Devil (Sat 27 July, 14:00). Written as an unofficial sequel to Daisies, and in keeping with the biblical allegory of Fruit of Paradise, Krumbachová takes the idea of pure evil and transposes it into the body of a gluttonous man. Another invasion of sorts, our female protagonist becomes almost a servant to the devil as she tries time and again to entertain him in her domestic space, only to realise that his desire is both destructive and insatiable.

Finally, in Rachel Maclean’s contemporary odyssey into the misogynist history of art and its affect on women’s self-esteem, Make Me Up (Fri 26 July, 12:00) we see themes of gluttony, decadence and resistance come full circle. Where appetites were once overindulged, Maclean’s women of the digital era are either rewarded for their obedience with processed rations or encouraged to show discipline and eat literally nothing at all. They are decorated like ornaments and expected to toe an Orwellian line, under the all-seeing eye of surveillance, 24-7. But even within a digitised world there are cracks – glitches that appear. And for all of the unbearably dystopic ideas these films throw up (sometimes literally), where there is even a glimpse of humanity, there is a resistance.

*Further reading: "Welcome to Society" by video essayist and programmer Jonathan Bygraves and "From 'soylent steak' to Soylent Green" by film historian Dr Peter Walsh.